Displays at the Powell Library

Three times a year, the Kitty King Powell Library presents a display of rare books. The displays, which often include related objects from the Bayou Bend Collection, are on view in Bayou Bend’s Lora Jean Kilroy Visitor and Education Center, on the second floor, during the library’s hours of operation.

The Good Child’s Library: 19th-Century American Children’s Publications from the Hirsch and Powell Rare Collections

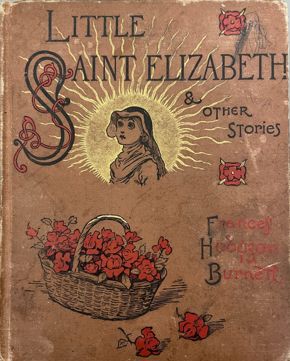

Little Saint Elizabeth and Other Stories, by Frances Hodgson Burnett, published by Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1890, Powell Library Collection.

“Curly Locks” from Mother Goose Rhymes, Jingles and Fairy Tales: Compiled from Authoritative Sources, published by the Henry Altemus Company, Philadelphia, 1896, Hirsch Library Collection, Gift of Michael Dale.

Kindergarten Occupations, Including Mats, Folding, Perforating, Sewing, & Mosaics, by Helen Stanley Dunbar, America, circa 1890, paper, cardboard, ink, linen, and silk floss, Powell Library Collection.

The Whale and the Perils of the Whale-Fishery, published by S. Babcock, New Haven, 1840, Powell Library Collection.

June 21–November 23, 2024

Taking its title from a planned series of children’s books by the Boston publisher E. O. Libby & Co., this display focuses on children’s books published in America in the 19th century from the Hirsch and Powell Libraries. Some of these books may be familiar to readers today—Mother Goose and Three Blind Mice are still around in updated forms—while others are unique to the 1800s, such as a book instructing children on the whaling industry.

As book publication became more affordable due to the industrial innovations of the 19th century, more people could afford to own books than ever before. Children’s books became popular gifts, as indicated by the inscriptions found in many of the books seen here from parents, relatives, and friends. Most of these books are educational—some expressly, such as the battledore for teaching the alphabet, and others less overtly, though even fiction for young people heavily emphasized the cultural values of the day.

This display, culled from the Powell Library’s rare book collection, overlaps with a related exhibition at Hirsch Library on Main Campus, Child’s Play: Artists as Children’s Book Illustrators, on view through December 7.

► Online

The virtual edition of The Good Child’s Library: 19th-Century American Children’s Publications from the Hirsch and Powell Rare Collections is available 24/7.

American Scenery: Bayou Bend Ceramics and Their Source Images from the Powell Library Rare Books Collection

Dinner Plate (detail), c. 1840–50, possibly by Coalport Porcelain Manufactory, after designs by William Henry Bartlett, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Bayou Bend Collection, Museum purchase funded by Mrs. Junius Estill.

William Henry Bartlett, artist, and Robert Brandard, engraver, The Horse Shoe Fall, Niagara, with the Tower, published in American Scenery; or, Land, Lake, and River …, by N. P. Willis, with illustrations by W. H. Bartlett. London: George Virtue, 1840.

Card Tray, c. 1840–50, by Chamberlain and Company, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Bayou Bend Collection, Museum purchase funded by the Bayou Bend Docent Organization.

William Henry Bartlett, Ascent to the Capitol Washington, published in American Scenery; or, Land, Lake, and River … by N. P. Willis, with illustrations by W. H. Bartlett. London: George Virtue, 1840. The Bayou Bend Collection, gift of Hirschl & Adler Galleries.

Coffeepot, Ralph Stevenson, decoration after Capt. Basil Hall, R. N., Cobridge, England, c. 1829–32, lead-glazed earthenware with transfer print, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Bayou Bend Collection, Museum purchase funded by Bill Porter in honor of Meredith J. Long at “One Great Night in November, 2010."

“The Mississippi at New Orleans,” by Basil Hall, published in Forty Etchings, from Sketches Made with the Camera Lucida in North America in 1827 and 1828. Edinburgh: Cadell & Co., 1830.

February 23–June 12, 2024

A multitude of picturesque scenic images embellished 19th-century English ceramics, appealing to a wide range of consumers. Rather than original designs, the sources for those images were usually prints published in books. American Scenery features four ceramic objects from the Bayou Bend Collection and their source images in rare books from the Powell Library.

After the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, vast markets for English ceramics opened up in North America, Europe, and India. Complete dinner sets or decorative pieces featured pictorial subjects copied from books, including natural scenery, towns, and buildings. Americans were eager to acquire ceramics displaying scenes of their own country, and books containing prints of American scenes provided fertile sources for English artists to copy. The artists making the copies inevitably made changes to their sources in the process, sometimes with only minor cropping or adjustments to fit the various shapes and sizes of the ceramic objects, but in other cases even adding or deleting elements for a picturesque effect.

Selling One’s Wares: A Selection of Trade Catalogues, Price Books, and Advertising from the Powell Library Rare Book Collection

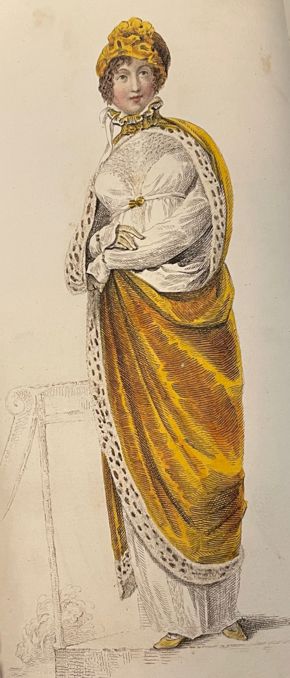

“Walking Dress,” The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashion and Politics, January 1809 issue, published by R. Ackermann in London, gift of Mrs. and Mrs. Fred T. Couper, Jr.; Mr. and Mrs. William T. Keenan; Mrs. and Mrs. Gregg Ring; and Mr. and Mrs. Robert D. Jameson.

Illustration of Ball, Black, & Co. earring, Demorest’s Monthly Magazine, December 1871 issue, published by W. J. Demorest in New York, gift of Phyllis Tucker.

Plate 101, untitled metalwork trade catalogue, c. 1780, published in Birmingham, England, gift of Susan Neptune.

Frontispiece, The Cabinet-Makers’ London Book of Prices, and Designs of Cabinet Work, Calculated for the Convenience of Cabinet-Makers in General: Whereby the Price of Executing Any Piece of Work May Easily Be Found . . . , 2nd ed., with additions1793, printed by W. Brown and A. O’Neil for the London Society of Cabinet Makers in London.

“Knife Rest,” Meriden Britannia Co. Gold and Silver Plate, 1886–87, published by Meriden Britannia in Meriden, Connecticut.

The American Storekeeper, January 1885 issue, published by the Holley Publishing Co. in Chicago.

October 18, 2023–February 17, 2024

Objects at Bayou Bend are often thought of primarily in terms of artistry and cultural history, but usually, they were also consumer goods. Long before the Industrial Revolution transformed the way consumers thought about and accessed material goods, anyone with a product to sell had to find ways to market that product. Selling One’s Wares focuses on the varied and changing means of doing so in England and America in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The earliest examples in this display of rare materials date back to the 1780s and include a price book, which allowed cabinetmakers to standardize prices. As printing grew more affordable, trade catalogs for retailers and consumers became common. Advertising, too, became more prevalent as the 19th century progressed, and the examples on display serve as early predecessors to today's ads.

Curtains and Cornices: The Art of Decorating Windows as Illustrated in the Powell Library Rare Book Collection

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashion and Politics, May 1, 1820 issue, “Window Draperies,” published by R. Ackermann in London, gift of Mrs. and Mrs. Fred T. Couper, Jr.; Mr. and Mrs. William T. Keenan; Mrs. and Mrs. Gregg Ring; and Mr. and Mrs. Robert D. Jameson.

Hepplewhite and Co., The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide: or, Repository for Designs for Every Article of Household Furniture…, 1788, “Cornices for Beds or Windows,” published by I. & J. Taylor in London, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert B. Jameson.

George Smith, Collection of Designs for Household Furniture and Interior Decoration, 1805, “Military Window Curtain,” published by J. Taylor in London

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashion and Politics, February 1, 1816 issue, “Drawing Room Window Curtains,” published by R. Ackermann in London, gift of Mrs. and Mrs. Fred T. Couper, Jr.; Mr. and Mrs. William T. Keenan; Mrs. and Mrs. Gregg Ring; and Mr. and Mrs. Robert D. Jameson

George Smith, Collection of Designs for Household Furniture and Interior Decoration, 1805, “Military Window Curtain,” published by J. Taylor in London.

Thomas Sheraton, The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book, in Three Parts, 1793, “Cornices, Curtains & Drapery for Drawing Room Windows,” published by T. Bensley in London, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert B. Jameson.

June 16–October 14, 2023

In early America, window coverings were a rarity and were usually very simple, until about 1800 when imported fabrics became more available and affordable. This change emerged in part because of the mechanization of textile production in Britain during the Industrial Revolution. British publications, inspired by French examples, helped to bring more-elaborate drapery designs to America.

The new styles included layered window curtains that could be looped back to the side, and valances—shorter draped fabrics—suspended from carved cornices at the top. Opportunities for decorative embellishments abounded with borders of contrasting color or trimmings of fringe and tassels, all of which could match or complement other upholstery in the room. Cabinetmakers recognized the importance of such draperies to an integrated interior, so they included examples in their published pattern books. Highlights of these exuberant window embellishments can be seen in design publications of the 18th and early 19th century from the Powell Library’s collection.

Nature Encased, Pressed, and on Display: 19th-Century Natural History in the Libraries Collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Shirley Hibberd, Rustic Adornments for Homes of Taste, A New Edition, Revised, Corrected, and Enlarged, 1870, “Fern Vase,” hand colored plate from drawing by H. Briscoe, published by Groombridge & Sons in London.

Shirley Hibberd, Rustic Adornments for Homes of Taste, A New Edition, Revised, Corrected, and Enlarged, 1870, “Entrance Hall, with Aquarium,” published by Groombridge & Sons in London.

Unknown creator, California Sea Moss, mid-19th century, museum purchase funded by Margaret Culbertson.

Algae collected and arranged by Eliza M. French in New London, Connecticut, 1849.

February 17–June 10, 2023

Shirley Hibberd, a prolific English writer on the subject of natural history in the 19th century, whose publications proved influential in America as well, believed that the study of nature and its inclusion in the home (in aquariums, fern cases, window gardens, birdcages, and such) was a means of both endorsing and enacting the correct morals of the late 19th century. He went so far as to state, “It would be an anomaly to find a student of nature addicted to the vices that cast so many dark shadows on our social life....”

Despite Victorian ideologies that positioned women as belonging to the private or domestic sphere, out of public life, women and girls were encouraged to engage in the study and display of natural specimens.

The MFAH libraries house numerous examples of the wave of interest in natural history that overtook England and America in the latter half of the 19th century, including examples of seaweed and floral collections of amateur naturalists, instructive books, and a trade catalogue for those interested in bringing nature inside their homes.

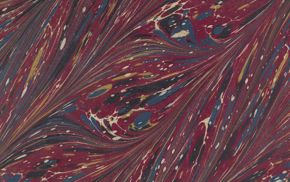

The Art of Clouds: Marbled Papers in the Powell Library Rare Book Collection

Marbled endpaper in the “Antique Modern” pattern, bound in the book Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue: The Industry of All Nations 1851, London: Published for the Proprietors by George Virtue, 1851.

View of workmen making marbled paper, 18th century, Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot, published 1751–72.

Marbled endpaper in the “Placard” pattern, bound in the book La Musica, Poema by Tomás de Iriarte, Madrid: Imprenta Real de la Gazeta, 1779.

Marbled endpaper in the “French Curl” pattern, bound in the book The World of Science, Art, and Industry Illustrated from Examples in the New York Exhibition, 1853–54, New York: Putnam, 1854.

Marbled endpaper in the “Fantasy” pattern, bound in a volume of the periodical The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashion and Politics, London: Published by R. Ackermann, 1809–28, bound by George Gregory, c. 1888–1920.

October 14, 2022–February 11, 2023

Marbled papers feature swirling patterns that suggest the natural beauty and mystery of clouds or water. Yet the patterns are actually formed through complex methods of floating paints on liquid in a tray and then gently laying paper on the paint. The practice, which goes back at least as far as 14th-century China, flourished in the 15th and 16th centuries in Turkey where it was called ebru, which translates as “the art of clouds.”

By the 17th century, the French established the use of marbled paper in bookbinding, and the method quickly spread to Britain and America. The tradition continues today in fine binding around the world.

The examples in this display date from the 18th and 19th centuries and demonstrate the range of patterns and colors used to adorn books of the period. These bindings, and the marbled paper used within them, are handmade custom work, rather than the standardized machine-made publishers’ bindings that transformed the practice of bookbinding in the 19th century.

Each page is unique, but the patterns—formed in the floating paints with comb-like tools of different sizes—bear names that are descriptive and sometimes exotic, such as “Antique Modern,” “Fantasy,” “Feather,” and “French Curl.”

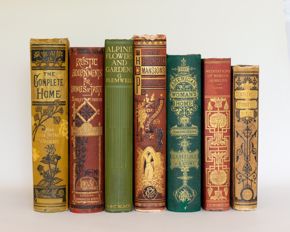

Pictorial and Ornamental Publishers’ Bindings: Decorated Book Covers from the Powell Library Collection

June 21–October 12, 2022

Industrialization and automation in printing and bookbinding radically transformed the publishing trade in America, leading to the golden age of publishers’ cloth bindings from about 1880 to 1920. Publishers recognized the commercial opportunities attractive book covers could generate, and with the help of artistic designers, the market flourished with beautiful, colorful, and affordable books. As artifacts, these cloth-bound books reflect the cultural shifts and art movements of the rapid industrial development and evolution of commercial binderies.

The main styles of cover design during this period tended to be ornamental or pictorial, the latter resembling decorative posters. Many designers incorporated their monogram or other symbol as a signature within the design. Thanks to these signatures and the visually distinctive styles some artists developed, the careers of such book-cover designers can be traced through their surviving work today. The Powell Library collection contains many examples from this period, and those on display include covers designed by the most successful and sought-after artists in the field, as well as examples by undocumented designers.

Ima Hogg after Bayou Bend: Selections from the Ima Hogg Papers at the MFAH Archives

Ima Hogg (center) with members of the 1972 Symphony Fund Drive, photograph by Tom Colburn, Houston Chronicle, MFAH Archives.

Van Cliburn and Ima Hogg, September 1971, Houston Chronicle photograph, MFAH Archives.

Ima Hogg and Ludy, 1975, MFAH Archives.

Ima Hogg and Kenny Sack, c. 1974, MFAH Archives.

February 12–June 16, 2022

In the words of Bayou Bend’s founding director, David Warren, Ima Hogg “took a new lease on life” after she moved from Bayou Bend in the fall of 1965 at the age of 83. She had spent years working to turn her home and her collection of American fine and decorative arts into a house museum, and in March 1966 her efforts came to fruition as Bayou Bend Collection and Gardens opened to the public.

In these later years, she was healthy and energetic and maintained a busy schedule of worthy projects and social activities. Her support of Bayou Bend continued, as did her long-term involvement with the Houston Symphony, and she also became engaged in new interests. The photographs in this display, taken between 1965 and 1975, support Warren’s statement and provide glimpses of this active, inquisitive, and generous woman in the last decade of her life.

Special items in the display include candid snapshots in her new apartment on San Felipe Street and with her pet Chihuahua, Ludwig van Beethoven, known less formally as “Ludy.” News photographers recorded her visit to NASA in 1967 and her presentation of a Steinway piano to the Houston Symphony in 1974. Also included is a copy of the program for the 1972 Houston Symphony Society Special Concert to honor her 90th birthday, with Arthur Rubenstein at the piano. These items are displayed courtesy of the MFAH Archives collections.

Ima Hogg before Bayou Bend: Selections from the Ima Hogg Papers at the MFAH Archives

Ima Hogg, age 12, photograph by William O. Journeay, c. 1894, Austin, MFAH Archives.

Photographs of Ima Hogg and her brothers (left to right), Will, Mike, and Tom Hogg, 1895, by William O. Journeay, Austin, MFAH Archives.

Inscription by Ima Hogg, age 8, 1890, Little Saint Elizabeth and Other Stories by Frances Hodgson Burnett, published by Charles Scribner’s Sons, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library.

Page from Ima Hogg’s sketchbook, c. 1896, MFAH Archives.

August 6, 2021–February 5, 2022

Ima Hogg, the collector and philanthropist who founded Bayou Bend Collection and Gardens, was born in 1882 in Mineola, Texas, to Jim and Sallie Hogg. As a young woman, she was already expressing interest in subjects that would later come to form a major part of her legacy, including art, music, public service, and devotion to her family.

Her interests are reflected in this selection of photographs, ephemera, and other objects she collected, on display courtesy of the MFAH Archives.

Ima Hogg before Bayou Bend focuses on her life prior to moving to Bayou Bend in 1928, especially in relation to her childhood, education, and early travels. The MFAH Archives collections include family letters and photographs, personal writing, souvenirs from trips, and from later years, records of her antiques-collecting career as well as the establishment of Bayou Bend as a house museum.

Tools of the Trade: Artisan Companions and Business Guides

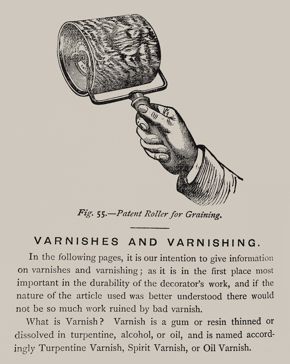

Charles Savory, The Paper Hanger, Painter, Grainer, and Decorator’s Assistant, 1879, engraving of a graining tool, page 136, published by Kent & Co., London.

February 5–August 6, 2021

Cabinetmakers, painters, and decorators in the 19th century had a plethora of manuals and guides from which they could learn and improve their skills. Publishing companies capitalized on this interest, and the Powell Library’s collection has numerous examples covering a range of trades during the 18th and 19th centuries. These books conveyed both the basic principles of a particular craft and the business of manufacturing. As a result, an artisan could confidently set up a business without the specialized training and experience otherwise required.

The volumes on view in Tools of the Trade represent common categories of 19th-century technical and industrial publications as related to the decorative arts: apprenticeship anecdotes; business advice; pattern and design examples; formulas and instructions; and material and labor costs. Also included are examples from one of the most prolific industrial and technical publishers in the United States: Henry Carey Baird.

Beautifully illustrated and occasionally annotated by the artisans who used them, these guidebooks enable researchers to learn more about the skills, techniques, equipment, materials, and business acumen of the craftspeople who created decorative arts objects in the Bayou Bend Collection.

“Wonderful Things”: Glass and Books Collected by Ima Hogg

Mary Harrod Northend, American Glass, New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1926, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library, gift of Ima Hogg.

October 1, 2020–January 30, 2021

Glassmaking is the oldest manufacturing industry in America, and glass objects were among the first American antiques collected by Ima Hogg. Her first major glass purchase in 1923 included an amethyst-colored pocket bottle, featured in this display. As she wrote her brother Will about the purchase, “... the things I thought so wonderful for which I paid so dearly! Nevertheless, I am the proud possessor of some rare specimens of Stiegel and Wistarberg glass.”

Ima Hogg studied any new collecting interest seriously, and she began acquiring books about glass in the early 1920s. Just before purchasing the amethyst bottle, she acquired Stiegel Glass, a limited-edition 1914 book about its maker. Upon the completion of Bayou Bend in 1928, she arranged her glass purchases on glass shelves in the Pine Room windows to take advantage of the light. Many remain there today. This display features several of her first acquisitions of glass, as well as the books she purchased to guide her glass collecting.

Limited Time Only: Rare and Delicate Materials in the Powell Library’s Rare Book Collection

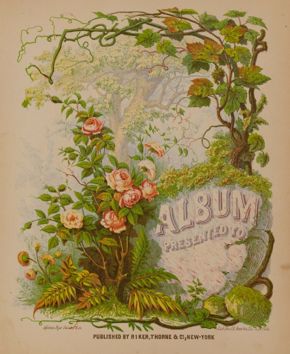

Alphonse Bigot, American Album, printed by A. Brett, Philadelphia, c. 1855, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library, gift of the 2018 Bayou Bend Docent Organization New York Travelers in honor of Susan Morrison and Barbara Fagan.

Allegorical Wood Cut with Patterns of British Manufacture in “The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions, and Politics,” first series, vol. 1, no. 1 (January 1809), published by R. Ackermann in London, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library.

Mary Lizzie Keller, Summer Hours, inscription and gouache painting in the Paragon Autograph Album owned by Beverly L. Stemmons, Dallas, July 24, 1881, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library.

“Currant” Flock Paper for General Purposes, manufactured by W. Woollams and Co., High Street, Marylebone, in “The Journal of Design and Manufactures,” vol. 4 (September 1850–February 1851), published by Chapman and Hall in London, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library.

February 4–August 22, 2020

For protective purposes, the Powell Library’s rare books are displayed only for limited periods of time, following the MFAH policies for works of art on paper. External factors, such as light exposure, or internal factors, such as the book’s paper and ink, can cause damage. These internal factors are known as “inherent vice” in libraries.

The rarely exhibited items in this display demonstrate the results of safe storage practices as well as inherent vice. Examples of the latter include periodicals printed on paper made of wood pulp, an innovation popularized in the publishing industry in the 19th century that allowed for cheaper printing, but that degrades much faster than earlier papers made of cotton rags.

Conversely, two 19th-century British periodicals contain fabric and wallpaper samples that remain in excellent condition, showing their original vibrant colors, because of their preservation away from light in bound volumes. After this display closes, the books return to the rare book stacks, where they are protected from light and fluctuations in temperature and humidity.

Feathered Glory: The Eagle as Represented in the Powell Library’s Rare Book Collection

Alexander Wilson, White-Headed Eagle (plate 36 in Wilson’s American Ornithology), hand-colored copper plate engraving, 1832, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library, gift of Thomas G. Jameson & Peter K. Jameson in memory of Robert D. Jameson, Jr.

Wilhelm Schimmel, Eagle, c. 1875–90, willow and eastern white pine, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Bayou Bend Collection, gift of Miss Ima Hogg.

Leonard and Wilson, Calling Card Case, c. 1847–50, silver, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Bayou Bend Collection, Museum purchase funded by Geroge S. Heyer, Jr. in honor of Wallace S. Wilson at “One Great Night in November, 2004.”

Susanna S. Johnson, A Drawing in Her Friendship Album, 1830, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library, gift of the 2018 BBDO Baltimore Travelers in honor of Cyril Hosley & Pamela Diehl.

October 1, 2019–January 25, 2020

Eagles figured prominently in American decorative arts of the 19th century, adorning silver and brass objects, ceramics, and furniture, while also appearing in three dimensions as weather vanes or ship figureheads. This display features images of the national bird of the United States found in Powell Library books, along with objects from the Bayou Bend Collection that were created during the first 100 years of U.S. history.

Moving far beyond the stylized frontal pose used in the Great Seal of 1782, the eagles in this display devour prey in realistic settings on the pages of John James Audubon’s and Alexander Wilson’s ornithological works. These eagles also spread their wings and appear with dynamic feathered glory on functional and decorative objects, asserting their owners’ pride in the new nation.

Leaving Your Mark: Inscriptions, Annotations, and Additions in the Powell Library’s Rare Book Collection

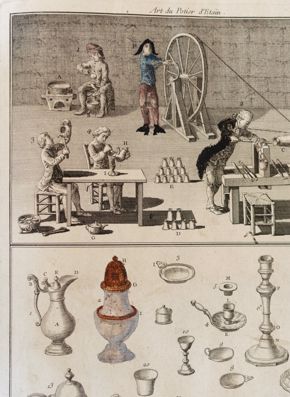

Pierre August Salmon, Art du potier d’étain, hand-colored plate, published by Chez Moutard, Paris, 1788, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library, funded by William J. Hill.

The New-York revised prices: for manufacturing cabinet and chair work, published by the New-York Society of Journeymen Cabinet Makers, printed by Southwick and Pelsue, New York, 1810, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library. (Notations by journeyman cabinetmaker Daniel Turnier)

George Washington, The President’s address to the people of the United States, September 17, 1796: intimating his resolution of retiring from public service, when the present term of presidency expires, printed for W. Young, Mills & Son, Philadelphia, 1796, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library. (Drawing of eagle by unknown artist)

Henry E. Chambers, A Higher History of the United States for Schools and Academies, published by F. F. Hansell & Bro., New Orleans, c. 1889, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library.

Henry E. Chambers, A Higher History of the United States for Schools and Academies, published by F. F. Hansell & Bro., New Orleans, c. 1889, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library. (Inscription to Ima Hogg from her father, James Stephen Hogg)

Frances Hodgson Burnett, Little Saint Elizabeth and Other Stories, published by Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1890, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library.

Frances Hodgson Burnett, Little Saint Elizabeth and Other Stories, Frances Hodgson Burnett, published by Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1890, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library. (Inscription by Ima Hogg, age 8)

Young Lady’s Own Book: A Manual of Intellectual Improvement and Moral Deportment, published by Thomas, Cowperthwait & Co., Philadelphia, 1838, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library.

July 16–September 28, 2019

Readers often leave their own marks on books in one way or another. Although librarians usually object to the practice, Leaving Your Mark presents examples of interesting marks and the stories they tell—or the mysteries they present.

People may inscribe books to commemorate special occasions, such as giving a book for a graduation or birthday, or simply to record ownership. Among the examples on view are books lovingly inscribed by a father to his young daughter (James Hogg to Ima Hogg), as well as a book that records an important meeting between Ima Hogg and her fellow collectors years later.

Sometimes marks reflect the owner’s profession, such as a cabinetmaker’s sketches and cost calculations in a cabinetmaking price book from the 18th century. Even collectors and curators mark the pages of auction catalogues as they search for new acquisitions.

Marks are not always in written form. The young owner of the 1838 etiquette book on display left the indentations of her fingers on the book’s cover, creating a tangible record of her presence—and raising several questions. Was the reader happily clutching the book tightly in her hands? Or do the marks indicate annoyance at being tasked to learn the rules contained within the book?

Printed Color for All: Chromolithographic Book Illustrations in the Powell Library’s Rare Book Collection

Scenery Autograph Album, title page, published in Boston, c. 1882, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library, gift of Nancy and Carter Hixon in honor of Margaret Culbertson.

Owen Jones, “Indian No. 6,” plate 54, The Grammar of Ornament, published by Bernard Quaritch, London, 1868, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library.

Alphonse Bigot, American Album, presentation page, printed by A. Brett, Philadelphia, c. 1855, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library, gift of the 2018 Bayou Bend Docent Organization New York Travelers in honor of Susan Morrison and Barbara Fagan.

“French Walnut,” The Art of Graining: How Acquired and How Produced ... with Lithographic Illustrations ... with 42 Colored Plates on Stone, Charles Pickert and A. Metcalf, authors, published by D. Van Nostrand, New York, 1872, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library, gift of William J. Hill.

“Rosewood,” The American Grainers’ Hand-Book: A Popular and Practical Treatise on the Art of Imitating Colored and Fancy Woods, published by John W. Masury & Son, New York, 1872, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library, gift of William J. Hill.

February 7–July 13, 2019

When Owen Jones (1809–1874) published the first edition of The Grammar of Ornament, he turned to the relatively new and expensive process of chromolithography. This method of printing could require up to 20 different lithographic stones, each with a separate color, printed one on top of another, producing intense and often subtly modulated tones. Chromolithography, or color lithography, grew into the most popular form of color book illustration in the second half of the 19th century, replacing hand-coloring with brighter and more consistent results.

Chromolithographs swept across America, decorating walls as well as book pages. These images delighted the public, even as leading moralists and intellectuals scorned what they saw as a debasement of high culture that became known as “Chromo-Civilization,” a term first used in 1874 in the magazine The Nation. The pioneering 1979 book The Democratic Art by Peter Marzio, director of the MFAH from 1982 to 2010, helped to establish chromolithography as a subject worthy of scholarly research and artistic appreciation.

Printed Color for All features a range of 19th-century chromolithographs that served artistic, educational, commercial, and decorative purposes. Chromolithography brightened the world of 19th-century Americans and continues to delight viewers today.

Houston Artists of the 19th Century in the William J. Hill Texas Artisans & Artists Archive

American, Purse, c. 1843, glass beads, nickel silver, and textile support, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Bayou Bend Collection, gift of William J. Hill.

Thomas Flintoff, Catholic Church, Houston, Texas, March 25, 1852, watercolor on paper, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Bayou Bend Collection, museum purchase funded by Cynthia and Anthony G. Petrello in honor of Carena Petrello at "One Great Night in November, 2007"

Made by Torrey & Brother, Pair of Tablespoons, c. 1843–1848, silver, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Bayou Bend Collection, museum purchase funded by William J. Hill in honor of David B. Warren

Telegraph & Texas Register (Houston, Texas), January 12, 1842.

Galveston Weekly News (Galveston, Texas), June 3, 1851

Guy & Cooke, Children of Willa Lloyd Jackson, c. 1892–95, San Jacinto Museum of History Library, gift of Mr. and Mrs. George A. Hill, Jr.

Portrait of Florence Datchelor by photographer C. J. Wright, c. 1875–78. Photographer’s imprint on the back of the photograph.

Houston Daily Mercury (Houston, Texas), October 21, 1873.

September 28, 2018–January 6, 2019

This display highlights Houston painters, photographers, and silversmiths of the 19th century, as well as handwork and needlework. The creators of many 19th-century Texas artworks are unknown, and even when artists’ names can be determined, information about their lives and creative output can be sparse and difficult to locate.

Bayou Bend’s William J. Hill Texas Artisans and Artists Archive unites documents and resources hidden in collections across the state to enable researchers to learn more about these artists and their world and gain a better understanding of their achievements. Named for the late Houston philanthropist and collector William J. Hill, the archive is intended to facilitate research and appreciation of Texas art and decorative arts. More than 100,000 records are online, and the collection continues to grow.

Complexity and Civility: American Victorian Dining Silver in the Bayou Bend Collection

Made by Whiting Manufacturing Company, Spaghetti Knife, c. 1866–80, silver, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Bayou Bend Collection, gift of Phyllis and Charles Tucker.

Eliza Cheadle, Manners of Modern Society: Being a Book of Etiquette, London, Paris, and New York: Cassell Petter & Galpin, c. 1872, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library, gift of Phyllis Tucker.

“Salts,” no. 28, Meriden Britannia Co. Gold and Silver Plate 1886–87 catalogue, Meriden, Connecticut: Meriden Britannia Company, 1886.

Gorham Manufacturing Company, Asparagus Tongs, 1870–75, silver and silver gilt, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Bayou Bend Collection, gift of Dr. William P. Hood, Jr.

Designed by George Wilkinson, manufactured by Gorham Manufacturing Company, Ladle, c. 1866, silver and silver gilding, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Bayou Bend Collection, gift of Phyllis and Charles Tucker

Owen Jones, “Egyptian No. 1,” Grammar of Ornament, London: B. Quaritch, 1868, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library.

American Etiquette and Rules of Politeness, Chicago: Rand, McNally & Co., 1883, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library, gift in honor of Phyllis Tucker.

May 15–September 8, 2018

The Victorian era encompasses the reign of Queen Victoria from her accession to the throne on June 20, 1837, until her death on January 22, 1901. British design and culture continued to influence America during this era in spite of American political independence. The display at the Powell Library focuses on silver cutlery that was made or sold in America, and reflects trends in dining, etiquette, and design in a uniquely American way. Design and etiquette books that fostered the creation and use of such objects are also featured.

Americans had imported much of their silver from abroad until the Tariff of 1842 imposed heavy taxes on imported goods and led to an increased focus on American silver production. American manufacturers looked to European design trends, often taking the form of various “revivals” of past styles including Rococo, Classical, and Egyptian.

Economic trends fostered the growth of a middle class eager to outfit their homes with furnishings that could project their status in the world. Etiquette books proliferated to help guide their readers through the formalities of social engagement, in which dining took on a major role.

Printed and Bound in Texas: Selections from the Powell Library’s Hogg Family Collection

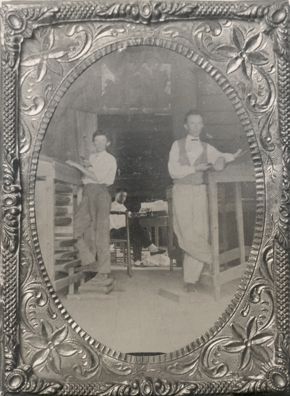

Governor James S. Hogg [on the right] as a young man, working on The Texas Observer, Rusk, Texas, ca. 1868. Courtesy of San Jacinto Museum of History

Sam H. Dixon, Poets and Poetry of Texas, Austin: S. H. Dixon Co., 1885, printed by Eugene Von Boeckmann; bound by Reinhard Von Boeckmann, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library, Hogg Family Collection.

John Henry Brown, History of Dallas County, Texas, from 1837 to 1887, Dallas, Texas: Milligan, Cornett & Farnham Printers, 1887, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library, Hogg Family Collection.

Biennial Report of the Secretary of the State of Texas, Austin, Texas: State Printing Office, 1892, bound by the D. & D. Asylum, printed by Ben C. Jones & Co., the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library, Hogg Family Collection.

John Wesley Hardin, Life of John Wesley Hardin, 1896, Seguin, Texas: Smith & Moore, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Powell Library, Hogg Family Collection.

February 23, 2017–May 14, 2018

Printing in Texas began on February 22, 1817, with a document printed by Samuel Bangs. Traveling as a printer for Francisco Xavier Mina’s expedition to Mexico, Bangs printed a manifesto for Mina using a portable printing press during a stopover on Galveston Island. Pamphlets, proclamations, proceedings and ephemera were characteristic of early Texas printed material through the 1820s, as entrepreneurs struggled to establish a permanent printing press on the sparsely populated colonial frontier. By the mid-1830s, printing presses across the state were issuing successful newspapers throughout the newly christened Republic of Texas. Shortly thereafter, these same enterprises offered bookbinding, stationery, and job printing, firmly placing printing among Texas’s bourgeoning trades.

Many well-known Texans engaged in printing during the 19th century. In 1835, Gail Borden Jr., along with his brothers, started the Telegraph & Texas Register at San Felipe. In the 1850s, Texas legislator John Henry Brown served as editor for newspapers in multiple Texas counties before writing several books on Texas history. In the mid-1860s, Governor James S. Hogg worked his first job as a typesetter for The Texas Observer, and it is Governor Hogg’s own collection from which this selection of printed material was chosen.