Separate Studies: Jack Whitten’s Untold Sculpture Practice April 25, 2019

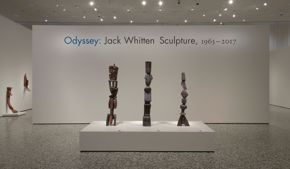

Installation view of Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963–2017.

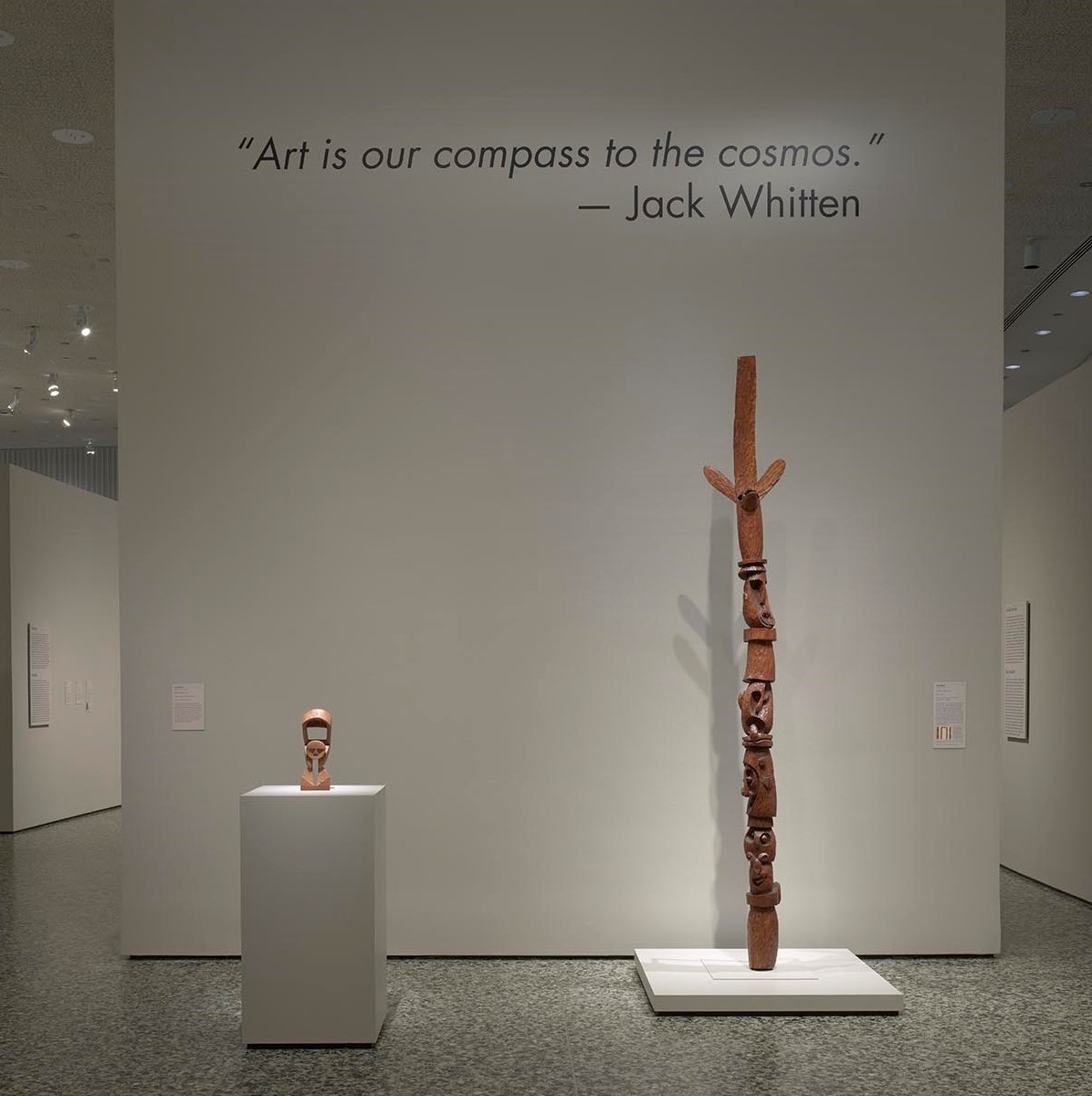

Installation view of Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963–2017, featuring Ancestral Totem (right).

Installation view of Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963–2017, featuring The Guardian I, For Mary (right).

Jack Whitten, Lucy, 2011, black mulberry, Phaistos Stone, mahogany, metal I-Beam, and mixed media. © Jack Whitten Estate. Courtesy of the Jack Whitten Estate and Hauser & Wirth

Jack Whitten, Lucy (detail), 2011, black mulberry, Phaistos Stone, mahogany, metal I-Beam, and mixed media. © Jack Whitten Estate. Courtesy of the Jack Whitten Estate and Hauser & Wirth

Installation view of Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963–2017.

Jack Whitten, The Afro American Thunderbolt, 1983–84, black mulberry, copper plate, and nails. © Jack Whitten Estate. Courtesy of the Jack Whitten Estate and Hauser & Wirth

Jack Whitten, a renowned painter recognized for his ingenuity and mesmerizing abstractions, also had a separate passion for sculpture. The exhibition Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963–2017 illuminates this separate—previously unknown—body of work, showcasing 40 sculptures crafted during his five-decade career.

Symbols and Surprises

Whitten (1939–2018) first began carving wood while he studied painting at Cooper Union in New York, to better understand African art both aesthetically and as part of his identity as an African American. An example is Ancestral Totem, which pays homage to his African and American ancestors. The totem features abstracted faces stacked on each other and is topped with a head of a llama—a symbol of intelligence and a self-portrait of the artist.

At the media preview for the exhibition, the artist’s widow, Mary Whitten, said “Just so you know, I always thought it was a deer … it’s a llama. Why he picked a llama? I don’t know. Surprises about him.”

Installation view of Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963–2017, featuring Ancestral Totem (right).

Ancient Traditions

Whitten’s sculpture practice expanded and ultimately flourished while he spent summers in Crete with his family. Inspired by ancient Cycladic and Minoan traditions, he created works that incorporated local and found materials, from wood and marble to bones and fishing lines.

Whitten’s reliquaries, such as The Guardian I, For Mary, illustrate these traditions by featuring items associated with his wife: locks of her hair, museum and bus tickets, animal bones, wild sage and olive leaves. Intended to protect her, the piece even includes a compartment with unseen contents, known only to the artist.

Installation view of Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963–2017, featuring The Guardian I, For Mary.

Rediscovered Treasures

Throughout his career, Whitten kept these two bodies of work separate. He would spend nine months of the year painting in New York, and three months in Crete exploring sculpture. Never meant to be exhibited, the sculptures primarily remained in Crete or displayed in the couple’s home.

“I had less of a connection to these early works because we were moving from house to house in Crete,” Mary Whitten said. “At that time, we would wrap them up and put them away in storage in someone’s barn and never look at them again for many, many years. It was kind of a revelation to find them again and re-see them.”

See Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963–2017 in the Law Building through May 27.