Archival Online Exhibitions

MFAH Archives

The MFAH Archives highlights its collections with online exhibitions. Drawing on a variety of documents—including photographs, letters, ephemera, and more—the exhibitions feature stories from the museum's rich history.

How Exhibitions Are Made

In the records of past museum exhibitions, a researcher can find a variety of treasures. Some of these gems one might expect to find, such as essays for the catalogue, press clippings, and checklists of artworks included in the exhibition. Additionally, the records often include project proposals, curatorial correspondence, interoffice memoranda documenting the planning of the exhibition, text of the accompanying wall labels, plot plans for of the precise placement of art in the gallery space, and press coverage.

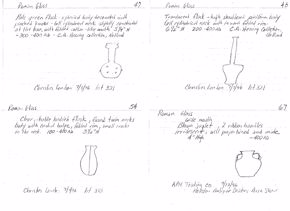

This image is from the archives for Glass of Imperial Rome from the John F. Fort Collection, exhibited in June 2002. The show was curated by Frances Marzio. Handwritten labels are paired with small drawings of the pieces included in the exhibition.

All great ideas begin somewhere. For an exhibition, it is with the project proposal. A curator drafts a proposal about why this particular exhibition will be beneficial to the museum. Sometimes, museums send out project proposals to other institutions to see if there is interest in participating in a traveling exhibition.

Initially, the plan is presented to a small group of staff. If approved, the proposal then moves on to a larger grouping of the staff before finally being accepted by the museum’s board. The proposal may be refined between meetings in order to gain approval.

Here is an example of a project proposal for The Splendor of Rome: The 18th Century (June 2000).

Checklists are a strong indicator of the progression of a show. As object loans get approved or denied and budgets become tighter, checklists grow and shrink. Often, if the exhibition is traveling, checklists vary depending on the venue. Museums may supplement the exhibition with relevant works from their own collections. Other works may not be permitted to travel due to conservation concerns or donor restrictions. The initial checklists can be very different than the final selection chosen for opening night.

This is a sample checklist from The Splendor of Rome: The 18th Century.

The amount of correspondence that revolves around an exhibition can be immense. There is contact between the curator and the donors, asking for financial support for a multitude of different aspects regarding the exhibition; the lenders, inquiring after certain pieces; and interoffice, working on the logistics to insure that the show is executed smoothly. Because exhibitions take a long time to plan, correspondence for a particular show can span several years.

The letter seen here was written by in 1930 by photographer Edward Weston to James Chillman, the founding director of the MFAH, agreeing to send the Museum some of his prints.

© 1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Plot plans provide a layout of where the objects will go in the museum space. Similar to an architectural drawing, in addition to showing where the objects are placed in the galleries, plot plans show doorways and walls, helping to illustrate the flow of the space. Knowing how objects are placed in relation to each other in the exhibition gives some insight into the curator’s intent for audience interaction. Plot plans have the potential for change based on recommendations by the installation team.

Generally, plot plans are found in the records of the office of the registrar. This plan for The Splendor of Rome: The 18th Century shows the layout of objects in the galleries.

Wall labels are the most effective way of relaying information about a piece of artwork to a visitor. Labels contain information such as a work's title, date of creation, artist, artist’s life span, and a small summary of information about the significance of the work.

These wall labels were created for The Draftsman’s Art: Master Drawings from the National Gallery of Scotland. They show the variety of labels that can be created for exhibitions: The first has more didactic information, while the second is a “tombstone” label, containing only essential information about the work of art.

Exhibitions are the culmination of years of research and planning, yet press coverage can be a major factor in determining the success of a show. The media can affect attendance, both in a positive and negative way. In some cases, what the press writes will influence the perception of a show years after closing. Press coverage serves to attract audiences but also to examine the themes of the exhibition. Success of a show is not only about the attendance numbers but also the ongoing conversation years later.

This quote from Anne Wilkes Tucker, curator of photography, reprinted above, shows that Robert Frank’s work in an exhibition had a lasting impact. Printed in the Houston Post, February 27, 1986.

Ultimately, it is the public that determines the success of an exhibition. Visitor comments are one tool for studying the public’s reactions. Comment books are an example of exhibition-related documentation found outside of curatorial and registrarial records.

Here is a page of the comment book from the exhibition British Designers: From Monarchy to Anarchy (November 2000). This shows some of the many types of people that come to exhibitions: This page includes a child’s handwriting, a note in Spanish, and a faint outline of a female figure.

Many museum goers use audio guides when visiting a new exhibition, particularly if the exhibition's subject is not well-known. Wtih audio guides, visitors are gently navigated through the galleries with experts sharing tidbits of knowledge. Audio guides indicate how the museum prefers patrons to interact with the exhibition and what they should leave the museum remembering.

The excerpt here is the script for the introduction to The Splendor of Rome: The 18th Century's audio tour.

Opening night is when the exhibition finally gets the spotlight. Paint is dry. Lighting is installed. Cases are sealed and frames are hung. The press has already gotten a sneak peek. Now, it's up to the art to shine.

Opening nights have many components. Different dinners honor lenders, donors, and guests of honor. Speeches and lectures have to be prepared, menus finalized, and guest lists double-checked. If there are multiple venues for an exhibition, there are multiple opening nights. Records pertaining to these celebrations can be found in the records of the development and curatorial departments.

This is the invitation for The Splendor of Rome: The 18th Century's opening dinner, hosted at Rienzi, the MFAH house museum for European decorative arts and paintings, the night before the exhibition opened to the public.

Since its foundation in 1900, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has hosted over 2,500 exhibitions. The exhibitions have ranged in size and scope over the years, growing as the Museum refined its record-keeping practices. The records of those exhibitions are housed in the Museum’s Archives, in both the registrar's (RG05) and curatorial (RG04) records. Related records can be found in marketing (RG11) and education (RG08). The records reveal how the Museum has changed under its many directors and curators and also reflect on the evolution of artistic movements.

Texas Art at the MFAH

From its earliest days as an outgrowth of the Houston Art League, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston championed the work of Texas artists. Emma Richardson Cherry, Julian Onderdonk, Edward “Buck” Schiwetz, Robert Joy, Mary Bonner, and Alexandre Hogue are among the prominent early Texans whose artwork was displayed in solo shows in the decade following the museum’s establishment in 1924. Shown here is a canvas fragment with an untitled original painting by Emma Richardson Cherry, an artist, educator, and founding member of the Art League. [MS08, Box 1]

The Annual Houston Artists exhibitions were held at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston from 1925-1960. Purchase prizes were awarded each year, with artwork selected to enter the museum’s permanent collection. The museum also sponsored the Texas General Exhibitions from 1940 to 1961 and Annual Exhibitions of Photography by Texas Photographers from 1926 to 1937. It frequently hosted the Southern States Art League Circuit Exhibitions between the years 1924 and 1943. A broad range of early artists from the Lone Star state were represented; most of these annual group exhibitions have been indexed by artist name and they are searchable at www.mfah.org/archives. [RG11.1, Series 2, Box 1, Folder 6]

For decades, self-described “painter/fisherman” Forrest Bess worked in isolation from his home studio in Bay City, on the very edge of the Gulf of Mexico. In 1941, and again in 1951, Bess showed his work at the MFAH in solo exhibitions organized by Director James Chillman. At the time of his first show, Bess was painting houses, dogs, and still lifes in something of a naïve impressionist style. By his second show he had devoted himself to painting symbolic abstractions which he called “ideograms,” based on the visions that plagued his sleep. Bess’s 1958 masterpiece “Untitled, No. 11a” entered the museum’s permanent collection in 1988. [RG05.01, Box 8, Folder 24]

At the twenty-fifth Annual Houston Artists Exhibition, the purchase prize was awarded to a new arrival to the city, a young professor at Texas Southern University named John Biggers who impressed the judges with his conte crayon drawing “The Cradle.” However, because African-Americans were allowed into the museum only on Thursdays, Biggers was not able to attend the reception given in his honor. Founding director James Chillman had expressed dissatisfaction with the social status quo since the early days of his directorship and seized upon the opportunity to fully integrate museum audiences. Biggers’ work celebrating African American history and identity would be featured prominently at the museum over the years, with 1954’s Paintings and Drawings by John Biggers and James Boynton followed by solo shows in 1962, 1968, and 1995. [RG05:01, box 7, folder 5, © John T. Biggers Estate/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY]

Working in concert with the Bank of the Southwest and the Oil Information Committee of Texas, MFAH Museum Director Lee Malone and the first Dean of the Museum School, Lowell Collins, organized Texas Oil ’58: A Salute to the Oil Industry of the State by Texas Painters. The exhibition was an early example of corporate sponsorship of the arts in Texas. After being displayed at the Dallas Public Library and the Republic National Bank of Dallas in September and October 1958, the exhibition was installed at the Bank of the Southwest in November. [RG05.1, Box 16, Folder 6]

Fifty-six Texas artists were represented in the Texas Oil show, including some who are still active today, such as Richard Stout, Henri Gadbois, and Leila McConnell. The $400 purchase prize was awarded to the now-obscure Fort Worth-based painter David Brownlow for his work “Project.” [RG05.1, Box 16, Folder 6]

Upon his appointment as Museum Director in 1961, James Johnson Sweeney brought with him from the Guggenheim both an aesthetic sophistication and a flair for dramatic installations. During his six-year administration the annual exhibitions of Houston artists were discontinued in favor of a regional juried show with the idea that locals would benefit from competing against a wider pool of talent. He purchased for the museum works by Houston-based artists Dick Wray and Richard Stout and organized exhibitions by faculty members from the museum school. Nevertheless, his perceived indifference to local art was lampooned in Frank Freed’s 1966 painting “Out!” in which Sweeney summarily dismisses a disconsolate artist and her humble landscape painting from a gallery hung with works by internationally renowned abstract expressionists. [Frank Freed, OUT!, c. 1966, oil on wood panel, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Eleanor and Frank Freed Foundation. © Estate of Frank Freed]

In the midst of the 1970s’ oil boom, Texas artists found increased visibility with the development of busy art departments at the University of Houston, Rice University, and the University of Saint Thomas, and a focused attention on Texas art at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. The MFAH refreshed its own commitment to local artists under the directorships of Philippe de Montebello and William Agee with notable shows by Dorothy Hood and Ary Stillman. In the spring of 1974, the MFAH’s Abstract Painting and Sculpture in Houston surveyed the work of some of the city’s leading practitioners, including Earl Staley, Dick Wray, Roberta Harris, Philip Renteria, Richard Stout, and Ben Woitena. In a press release, E.A. Carmean, Jr., the museum’s Curator of Twentieth-Century Art, remarked that the exhibition was “designed to show not young, emerging talent, but rather, those working for a sufficient time to develop a vocabulary.” [Installation photo by Alan Mewbourn. Photo Collection, Installation Views, Box 34]

In 1985, the MFAH mounted a dramatic show of work by local artists entitled Fresh Paint: The Houston School. Forty-four painters were represented in the survey, from senior artists like Charles Schorre, Joseph Glasco, and John Biggers to established, mid-career artists such as John Alexander and Gael Stack, as well as new talents including Sharon Kopriva and Kelly Alison. Organized by Curator of Twentieth-Century Art Barbara Rose and art critic Susie Kalil, the exhibition received national attention and is still perceived as a landmark event in the history of Houston’s homegrown art scene. In this photo, Mayor Kathy Whitmire addresses guests at the show’s opening and proclaims January 25, 1985 “Fresh Paint Day.” [Photo by Chris Crane. Photo Collection, Events, Exhibition Openings, Box 2]

Curated by Alison de Lima Greene, 1990’s Tradition and Innovation: A Museum Celebration of Texas Art drew from the museum’s own collection, with forty painters and sculptors represented. “The exuberance, the quality, and the vitality of Texas art gives us a fresh view of the character of this region,” wrote Greene. “As a part of an ongoing dialogue between artist and public, studio and museum, this exhibition hopefully will extend the borders of Texas.” A second exhibition of Texas art from the collection, Myths and Realities, was shown five years later. Pictured at the 1990 opening, from left, are Mel Chin, Randy Twaddle, Ibsen Espada, Dorothy Hood, James Surls, Charmaine Locke, Earl Staley, Salle Vaughan, Charles Schorre, Gilles Lyon, Michael Golden, and Derek Boshier, whose painting “Everyday Opera” is partially visible. [Photo by Tom Dubrock. Photo Collection, Events, Exhibition Openings, Box 2]

John Alexander moved to New York City in 1979, but the swamps and Piney Woods near his native Beaumont continue to influence his art, including his 1982 painting “Mr. Friend’s Revenge,” a gift to the museum from longtime supporters Isabel B. and Wallace Wilson which was displayed in 1995’s Texas Myths and Realities. Alexander’s work has been featured in four group shows at the museum as well as a major retrospective in 2008 curated by Alison de Lima Greene. [John Alexander, “Mr. Friend’s Revenge” 1982, Gift of Isabel B. and Wallace S. Wilson, 83.39, © John Alexander]

In 2000, selections from the museum’s holdings of Texas art were compiled in a 279 page, full-color catalog entitled Texas: 150 Works from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Curator Alison de Lima Greene’s text provides an overview of the museum’s history of acquiring Texas art and analyzes the work’s power to transform the state’s landscape into the mythic and spiritual, with an emphasis on modernist and postmodernist aesthetics. Shown here is designer Don Quaintance’s alternate cover scheme featuring Mel Chin’s Terra Infirma [Untitled], which was ultimately rejected in favor of a design based on Forrest Bess’s Untitled, No. 11a. [RG4.03.05, Box 1, Folder 13]

As The Art Guys, Jack Massing and Michael Galbreth have become two of Houston’s most well-known artists. They delight (and sometimes disturb) an unsuspecting public while expanding the boundaries of art with their installations, sculptures, performances, drawings, and video work. For their 2001 piece SUITS: The Clothes Make the Man, the Art Guys explored the intersection of art and commerce by traveling the country in finely tailored men’s wear emblazoned with corporate logos. The tour culminated in an exhibition of drawings, ephemera, and of course, the suits themselves, which entered the MFAH’s permanent collection. In this photo, the Art Guys pose with Governor Ann Richards at Vespaio Ristorante in Austin. [MS37, Series 7, Box 7, Folder 4]

Since its inception in 1925, the MFAH has had a rich history of collecting and exhibiting work by Texas artists. The Museum has presented more than 325 shows by artists from the Lone Star State, and the MFAH collections include some 2,000 paintings, sculptures, drawings, and prints by Texas artists. Peter C. Marzio, the Museum’s director from 1982 to 2010, wrote that the works “not only offer a vivid portrait of the state seen through the eyes of its artists, but also challenge us to readdress our assumptions about regional art.”

Wartime Records in the Collection of the MFAH Archives: Exploring the Intersection of War and the Art Community

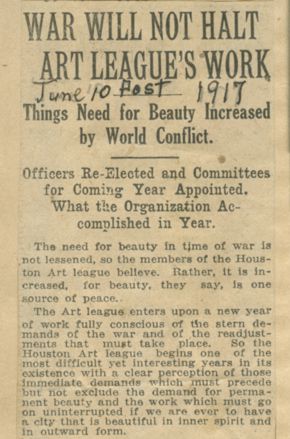

“War Will Not Halt Art League’s Work”, RG17 Houston Art League records, Scrapbook p.68, MFAH Archives.

This brief article published as the United States entered World War I defines an essential, rather than diminished, societal role for art in times of conflict. Through archival holdings dating from World War I to the present, this online exhibition will explore the various war-time roles adopted by the individuals and organizations that comprise the art community.

“The Place of the Museum in Time of War”, excerpt from MFAH President Ray Dudley’s radio address April 12, 1942. RG01 Trustee records, Annual report, Summer 1942, MFAH Archives

This excerpt of MFAH President Dudley’s address, reprinted in the MFAH’s Summer 1942 annual report, elaborates on earlier sentiments as the United States stood again on the brink of world war.

Mike Hogg’s Company, Texas Brigade, prior to deployment, c 6/1917, annotated MS2111_0200020150, MS21 Ima Hogg Papers, WWI letters, MFAH Archives.

In his letters home, Mike Hogg (1885-1941) wrote admiringly of French architecture, countryside, and children. In the early days of his deployment, he found time for language lessons and a musical band. Of the soldiers he commanded in the Texas Brigade, 90th Division, 360 Infantry, he wrote “[they came] from the East Texas counties – Trinity, Angelina, Walker, Montgomery, and Polk”. They ultimately fought in the Meuse-Argonne offensive, collapsing the last German defense line and bringing about the armistice, November 11, 1918. Although less involved with the museum than his brother Will, the driving force behind the 1924 capital campaign, and his sister Ima, donor of Bayou Bend Collection and Gardens, Mike served on the MFAH’s board from 1939 until his death.

Excerpt from Stella Hope Shurtleff’s letter to Texas Art Association, 9/28/1918. RG19 Houston Art League, Miscellaneous Subjects, Correspondence of Stella Hope Shurtleff, MFAH Archives.

During WWI, many art museums, as well as the American Federation of Arts, circulated numerous exhibitions based on patriotic war themes. In 1916, the MFAH held “Paintings by French Soldier-Artists” during which patrons could purchase the exhibited works, a not uncommon practice during the days of the Houston Art League. In this excerpt from a letter to the Texas Art Association, League member and art lecturer Stella Hope Shurtleff comments on an exhibition of aerial war photography, a new phenomenon made possible by the introduction of warfare flight.

Thomas Hart Benton, “The Sowers”, 1941-1945. ARC Identifier 515648 / Local Identifier 44-PA-1966 Photographs and other Graphic Materials from the Office for Emergency Management. Office of War Information. Domestic Operations Branch. Bureau of Special Services. (03/09/1943 - 09/15/1945) National Archives and Records Administration

American artists used their talents to support the war effort during WWII in various ways. Paul Manship joined in organizing “Artists for Victory” that sponsored a war poster competition at the Museum of Modern Art, a contemporary art exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and a juried exhibition of prints at the MFAH that opened simultaneously in twenty-four cities nationwide. Although not a member of the group, Thomas Hart Benton graphically conveyed a dire warning against the Third Reich.

“Notes on Houston Artists in Service”. RG01 Trustee records, Annual report, Winter 1945, MFAH Archives.

Local artists were called into service during WWII, both in active duty and as civilians. On the home front, artists volunteered at Ellington Field, constructing models of airplanes and the city of Tokyo.

Brigadier General Maurice Hirsch in WWII photo inscribed to future wife. MS16-001-001, MS16 Maurice and Winifred Hirsch Papers, Photography, MFAH Archives.

Brigadier General Maurice Hirsch (1890–1983) volunteered in both World Wars - in WWI on the War Industries Board and in WWII as chair of the War Contracts Price Adjustment Board and Renegotiation Division director. He saved the US over 11 billion dollars, earning him the Distinguished Service Medal in 1945. Upon leaving active duty in 1947, he married Winifred Busby, and embarked on a life of travel and philanthropy centered on the arts. Maurice served as president of the Houston Symphony Society and as a member of the Metropolitan Opera Association and the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art. The Hirsches’ involvement with the MFAH began in 1951 and led to their roles as life trustees and their endowment of the museum library in 1981. Maurice promoted cultural exchange with Italy and Japan, earning the Italian Star of Solidarity medal (1957) and the Third Class Order of the Sacred Treasure (1981) for his work as founding president of the Japan-America Society of Houston.

MS28 Series 6 – Foster Plan letter to Eleanor Freed. MS28 Frank Freed and Eleanor Freed Stern Papers, MFAH Archives.

Eleanor Freed, art columnist for the Houston Post in the 1960s and 1970s, and her husband, Frank, were fixtures on the nascent Houston contemporary art scene of the mid-20th century. The Freeds also supported many humanitarian causes. Following WWII, Eleanor joined the Foster Parents Plan, providing support for a young French girl, Monique, in the war-torn Normandy village of Merville. Monique, who refers to Eleanor as her godmother, sent her this letter and drawing; in a post-script, her mother explains that the drawing is of the Merville church that was nearly destroyed in 1944 during the American liberation of the Dieppe region.

Harris Masterson III, in military dress. MS32-014-400.02, MS32 Harris and Carroll Sterling Masterson Papers, MFAH Archives.

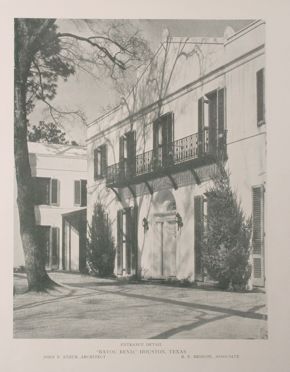

Having served as an intelligence officer in WWII, native Houstonian and philanthropist Harris “Harry” Masterson III served as an instructor at the rank of captain at Fort Riley, Kansas, during the Korean conflict. In 1951, he married Carroll Sterling Cowan. At the end of 1952, the Mastersons returned to Houston and began a relationship with the MFAH that spanned several decades. They also became avid supporters of the visual arts and lavish entertainers. In addition to gifts of art and donations made to the MFAH over the years, the Mastersons gave Rienzi, their River Oaks home designed by architect John Staub, to the museum in 1991. The prior year, they had received the National Medal of Arts.

Still from “Road to the Olmec Head”, 1963. Produced and directed by Richard de Rochemont. AVRG02-00004-01, RG02:03 Office of the Director, James Johnson Sweeney, MFAH Archives.

In 1949 the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) launched a covert operation entitled Congress for Cultural Freedom that funded arts projects in European and other countries. Designed to juxtapose Western artistic expression and the oppressive Stalinist regime, the operation bankrolled exhibitions, performances, films and the journal, Encounter. Richard de Rochemont, who had produced a short film entitled The Cold War in 1948, worked with his brother Louis on the March of Time newsreels of the 1930s and 1940s. It was Louis who was chosen to produce the CIA-funded Animal Farm in 1953. In 1963, Richard de Rochemont produced The Road to the Olmec Head, that documented the excavation of an ancient Olmec head in Mexico and its transportation to the MFAH. The CIA’s covert operation ended in 1967 as a result of exposure in the press.

Schedule from Fall Film Festival 1974 listing In the Year of the Pig directed by Emile de Antonio. RG04:13 Curatorial Department, Film and Video, MFAH Archives.

The controversial anti-war film about Vietnam, In the Year of the Pig, by Emile de Antonio was nominated for Best Documentary Feature in 1969 by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. When it was originally released in 1968, theaters showing the film faced intimidation. In California, a screen where the film was to be projected was vandalized with a tar-painted hammer and sickle. A bomb threat against theaters in Houston caused the showing to move locations twice.

The film played shortly after the Brown Auditorium was completed at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston in 1974, ironically, the year between the signing of the Paris Peace Accords and the fall of Saigon.

“Afghanistan: A Timeless History”, November 17, 2002 – February 9, 2003, installation view. RG36-1022-001, Photographer Thomas R. DuBrock, MFAH Archives.

This exhibition celebrated the Afghan artistic legacy, that had been the target of Taliban censorship. The exhibition paid tribute to the monumental Buddhas at Bamiyan, which were purposely destroyed by the Taliban in 2001. They are represented in their pre- and post-Taliban states at the entrance to the exhibition. The National Museum of Kabul lent the MFAH objects that presented the diversity and beauty of the art of Afghanistan. The Afghan staff, at great personal risk, had preserved the art collection during years of Taliban rule, factional fighting, and looting.

Press release announcing MFAH’s participation in Blue Star Museums, 5/22/2012. RG08:02_20120502, Marketing Records, Press releases, MFAH Archives.

In 2010 the National Endowment of the Arts (NEA), in collaboration with Blue Star Families and the U.S. Department of Defense, launched Blue Star Museums, an initiative to provide free museum admission to the nation’s active duty military and their families during the summer months. In May of 2012, the MFAH announced its participation in the program. Over the course of the summer, the number of Blue Star Museums grew from 1,500 to 1,800. A member of the 147th Reconnaissance Wing at Ellington Field thanked “those agencies/organizations [that] make efforts to help out military families with programs such as the Blue Star program,” writing “My family and I enjoy the arts and will utilize the free admission.” Nearly 1,000 troops and family members took the occasion to visit the MFAH, which also offers half-priced general admission tickets year-round to active, reserve, and retired military personnel and their spouses.

Through archival holdings dating from World War I to the present, this online exhibition explores the various wartime roles adopted by the individuals and organizations that comprise the art community. It correspondes with the MFAH exhibition WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath, an unprecedented look at the experience of war through the eyes of photographers, which was on view from November 11, 2012, through February 3, 2013.

The Garth Clark Gallery Archive: From the 20th Century into the New Ceramics Millennium

Garth Clark (left) with Mark Del Vecchio. MS61 Garth Clark Gallery archive, MFAH Archives

Beginning in the 1960s, collectors Garth Clark and Mark Del Vecchio assembled over five decades an unparalleled collection of modern and contemporary ceramics, focusing on objects that individually and collectively challenge traditional expectations of the medium. Here the collectors are pictured with the work of Alev Ebüzziya Siesbye.

Garth Clark Gallery newsletter, February 9, 1984. MS61 Garth Clark Gallery archive, MFAH Archives

In one of the early newsletters sent out from the Garth Clark Gallery after the opening of their New York space, Clark writes “The new space is doing very well. We have had an excellent response from our peers in the art world and the gallery design even came in for some very flattering praise from Clem Greenberg.” The Garth Clark Gallery newsletters are a rich source of information, documenting the history of contemporary ceramics in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s.

Card from artist Akio Takamori to Garth Clark. © Akio Takamori MS61 Garth Clark Gallery archive, MFAH Archives

A 1985 Garth Clark Gallery news bulletin describes Akio Takamori : “…a controversial young ceramist working both in the United States and Japan. His work is highly erotic and charged with ambiguity and ambivalence. Takamori literally draws figures into his thin envelope shaped vessels using the lip and silhouette of the pot freely as a pictorial device.” In the 1990s, his work moved from vessels towards more figurative sculptural works. The Garth Clark Gallery archive documents this progression of Takamori’s artistic style through photography, exhibition materials and correspondence.

Exhibition designed by Peter Struycken. Haenen artwork © Babs Haenen. Photographer: ©Noel Allum. MS61 Garth Clark Gallery archive, MFAH Archives.

This is an installation view of a Garth Clark Gallery exhibition of work by Babs Haenen, a Dutch ceramicist with a long relationship with the gallery. Janet Koplos wrote of this exhibition of Haenen’s works: “They evoke an architecture of melting, swelling, fracturing forms…. Her dazzlingly fluid forms were extremely well served by Struycken’s restrained, nuanced, astute color environment.” From Art in America, April 2000.

Installation view of group exhibition at Garth Clark Gallery. Art objects, © Lydia Buzio, © Akio Takamori , © Estate of Ralph Bacerra, ©Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts & Happy Valley Foundation. MS61 Garth Clark Gallery archive, MFAH Archives.

Over six hundred exhibitions have been presented from the Garth Clark Gallery spaces in New York, Los Angeles and other venues serving an international audience of collectors and museums. Group shows such as this one brought together the works of some of the most important artists in modern and contemporary ceramic art.

Ruth Duckworth in studio, 1999. Art objects © Estate of Ruth Duckworth, courtesy Thea Burger . MS61 Garth Clark Gallery archive, MFAH Archives

An article in Ceramic Arts Notes, April 6—May 22, 1999, preceding the Garth Clark Gallery exhibition Ruth Duckworth at 80 states, “Her large studio in Chicago, a converted pickle factory, is filled with half completed experimental forms that were destined for this exhibition. Some ideas made it to the final cut and others were abandoned. …. For those who have followed her long career, the fact that this show includes so many new forms will come as no surprise.”

MS61 Garth Clark Gallery archive, MFAH Archives

Potter Michael Cardew discussed his techniques and philosophy in the slide presentation Michael Cardew: A Coffeepot, “You’ve got to center it, just as if it were a pot. And in it, you will see it running smoothly through your fingers…. Well, it doesn’t look much you see as it is now, but a coffee pot is a kind of difficult proposition from the point of view of design, because when you’re making a pot, what you’ve got to remember is what’s it going to look like when you’ve got [the] spout added and more, it’s got to have a lid. All of which is going to modify the original shape you make.”

Symposium brochure The Yixing Teapot, December 7th, 1992. Art object © Ah Leon, Taiwan. MS61 Garth Clark Gallery archive, MFAH Archives

The Garth Clark Gallery was also well known for its contributions to ceramic scholarship through publications and symposia such as The Yixing Teapot. It was “the first symposium in the United States to deal specifically with the Yixing teapot in the 20th century. Yixing, a province of China, produced the first teapots to reach the West in the 17th century and has subsequently influenced ceramic design internationally. The hallmarks of the aesthetic are an unglazed surface that showcases the fine-grained clay and a refined surface, often with realistically rendered detail.” –from symposium brochure The Yixing Teapot, December 7th, 1992.

Cover of Ceramic Millennium Leadership Congress for the Ceramic Arts Report, 1999. MS61 Garth Clark Gallery archive, MFAH Archives

At the beginning of the Ceramic Millennium Leadership Congress, Garth Clark spoke of the changes taking place in the ceramic world, “In modern times there have been two seismic shifts in the status of ceramics in our society. The first was the impact of industrialization in the 18th century which for its ills brought us a sophisticated new approach and understanding of ceramics. The second was the emergence of the arts and crafts movement in the 19th century, which rescued ceramics from industrial anonymity and restored it to the individual. Now in the ebbing light of the twentieth century, the arts and crafts movement, the main engine of the ceramics movement has run out of steam and we see another profound change, a movement away from specialization. Ceramics may become just another choice in a menu of media from which any and all artists can select. If this is indeed the case, if this shift is more than just a short term fad, then it will be one of the most challenging steps yet for the aesthetic role of ceramics in our society.”

Preliminary sketches for an upcoming ceramic work by Jean-Pierre Larocque. © J.P. Larocque. MS61 Garth Clark Gallery archive, MFAH Archives

Artist Jean-Pierre Larocque pondered his idea for a teaset, writing to Garth Clark, “A teaset on the back of a horse is out of the question. So is a horse in the shape of a teapot. I like a horse carrying a covered cistern or large jars on each side but it is hard to see a live animal carrying gallons of boiling tea. Water supply maybe. What about a work horse loaden[sic] with merchandise., bundles of tea leaves, dry goods, hundreds of pots roped together. What if the horse pulled a cart. . . . U-haul on the silk road . . . loaded with tea merchandise.”

The exhibition Adrian Saxe: New Works was one of the inaugural Garth Clark Gallery exhibitions in New York in 1983. Saxe was the first artist to work at the Atelier Experimental at the Manufacture Nationale de Sevres. The fall 1998 Ceramic Arts Newsletter published by Garth Clark Gallery states, “In talking of Saxe, critic Christopher Knight made the welcome pronouncement that after a long battle, and although still marginalized, ‘Pottery has become recognized as an art form.’”

Garth Clark and Mark Del Vecchio amassed one of the most important collections of modern and contemporary ceramics in the world. The collection includes objects that date from 1940 to the present and holds more than 375 international works. Asian, African, and Latin American artists are represented, but European and American artists form the core of the holdings. In-depth surveys of artists such as Marek Cecula, Ruth Duckworth, Laszlo Fekete, Ken Ferguson, Anne Kraus, Richard Notkin, Akio Takamori, Beatrice Wood, Betty Woodman, and others demonstrate the range of artistic expression within the field and over the course of an artist´s career. Additionally, the collection contains work by artists who are known primarily for sculpture and painting but who also worked in clay, such as Arman, Sir Anthony Caro, Lucio Fontana, Roy Lichtenstein, and Claes Oldenburg.

The Garth Clark Gallery Archive at the MFAH contains a wealth of information documenting the progression of modern and contemporary ceramics from the late 20th century into the 21st. The archive comprises artists' correspondence, gallery and press materials, publications, exhibition records and ephemera, photographs, and audio-visual materials.

Moments from MFAH History

RG19:05, box 3, folder 29

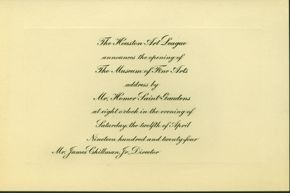

When director Peter C. Marzio arrived at the MFAH in 1982, one item on the top of his agenda was the establishment of an archival program. In support, the museum trustees initiated a survey of the MFAH's historic records then scattered among office spaces and storage areas. The survey revealed that the MFAH's historic record was largely intact, with the earliest records dating to the formation of the museum's founding organization, the Houston Public School Art League in 1900. Five years following the opening of the museum’s first permanent building in 1924, the League officially amended its charter to adopt the name Museum of Fine Arts of Houston, later changed to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo shows the invitation to the opening of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s first permanent building, April 12, 1924.

Photo: Sarah Shipley, RG19:06-001

The League first incorporated in 1913 under the official name, the Houston Art League, a change which reflected its broader mission of building a permanent art collection and introducing exhibitions to the city’s general populace. The League dedicated the site for the museum’s first permanent building in 1917 and re-dedicated it each year until construction began in 1923.

The original dedication marbles were recently transferred to the care of the MFAH Archives.

RG05:01, box 7, folder 59

The Annual Houston Artists exhibitions were held from 1925-1960; art work from the annual exhibitions were selected to enter the permanent collection as purchase prizes. Other long-running annual shows were the Texas General Exhibitions, 1940-1961, and the Southern States Art League Circuit Exhibitions, which were frequently shown at the MFAH from 1924-1941. The majority of annual and group exhibitions in the MFAH’s history have been indexed by artist name and are searchable at www.mfah.org/archives.

In 1950, John Biggers’s capture of the purchase prize for the Annual Houston Artist exhibition heralded the end of segregation at the museum. Founding director, James Chillman, who had expressed dissatisfaction with the social status quo early in his directorship, took this opportunity to fully integrate museum audiences.

MS19-58

The foundation of the MFAH’s pre-Columbian art collection was established in 1965 with a large donation of objects from Alice Hogg Hanzen. Married to Mike Hogg from 1929 until his death in 1941, Alice remained close to Ima Hogg throughout her life. A life trustee, she also maintained close ties to the MFAH and Bayou Bend Collection and Gardens. Her niece and life trustee, Alice C. Simkins, carries on the family legacy, which is chronicled in a permanent installation at the Lora Jean Kilroy Visitor and Education Center. Photo shows Alice Hogg Hanszen at her Mexican ranch, c. 1930s.

RG05:01, box 8, folder 18

The MFAH's early exhibition history focused on American art and modernism as well as regional and Texas art. Houston's early interest in Latin American art is also reflected in the exhibition history. When Diego Rivera penned this letter in 1951, it was in preparation for his first solo exhibition at the MFAH. His works had previously been exhibited in six group exhibitions at the MFAH from 1927-1947.

Photo: The White House, RG35-046:02-001

The former home of life trustee Ima Hogg, Bayou Bend, was donated to the museum in 1957, followed, in 1962, by the donation of its collection of paintings and decorative arts. The 28-room mansion was designed by well-known Houston architect John F. Staub in 1927 for Ima Hogg and her brothers. Following the marriage of her brother Mike in 1929 and the death of Will in 1930, Ima remained at Bayou Bend developing its exceptional collection of American decorative arts as well as cultivating its 14 acres of formal and woodland gardens. Bayou Bend Collection and Gardens, which opened to the public in 1966, is on the National Register of Historic Places. The new Lora Jean Kilroy Visitor and Education Center welcomes visitors to the site and accommodates educational activities.

Bayou Bend served as the site of an official dinner for the delegation heads at the 1990 Economic Summit of Industrialized Nations, photographed here on the north lawn. From left to right: François Mitterand, Jacques Delors, Helmut Kohl, Giulio Andreotti, George H.W. Bush, Margaret Thatcher, Brian Mulroney and Toshiki Kaifu.

Photo: Allen Mewbourn, RG05-255-005

The open expanse of the second Mies van der Rohe addition, the Brown Pavilion, doubled the museum’s existing gallery space. When the Pavilion opened in 1974, Mies had been dead for five years; however, the structure remained true to his plans. The construction of the Brown Pavilion was overseen by MFAH director, Philippe de Montebello, 1969-74, who successfully launched and concluded what at the time was the largest capital campaign in MFAH history. The Brown Foundation, Inc. contributed millions toward the construction and operating endowment of the wing named in its honor. The photo shows the Brown Pavilion during the inaugural exhibition, The Great Decade of American Abstraction: Modernist Art 1960 to 1970, 1/14-3/10/1974.

MS58:03.02, box 6, folder 15

Under the directorship of William C. Agee, 1974-1982, a curatorial position for photography was created. Headed by Anne Wilkes Tucker, photography would become a major strength of the permanent collection. In 2002, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston acquired nearly 4,000 photographs from Dutch collector Manfred Heiting. Over thirty years Heiting, named one of America´s top 100 art collectors by Art & Antiques magazine in 2003, amassed a comprehensive collection that includes the works of nearly every major photographer and documents the development of the art of photography. In 2006, Manfred Hieting donated his papers chronicling the development of his collection to the museum archives.

Photo: Richard Cunningham, RG04-464-002

Shortly after director Marzio’s arrival, he invigorated the Lillie and Hugh Roy Cullen Sculpture Garden project. Completed in 1986 by renowned landscape artist, Isamu Noguchi, the sculpture garden gracefully connects the space between the Caroline Wiess Law building and the Glassell School of Art. Itself a work of art, the garden is defined by shapes created with its foliage, pathways, and earthen mounds juxtaposed against walls of various shapes and heights that provide an undulating, dynamic backdrop for the more than 25 sculptures it contains. Here, Peter C. Marzio and Isamu Noguchi discuss the sculpture garden during its construction, 1985.

Photo: unknown photographer, MS32-109-07

Rienzi, the MFAH house museum for European decorative arts, opened to the public in 1999. Harris and Carroll Sterling Masterson donated their home, named after Harris Masterson's maternal grandfather, Rienzi Melville Johnson, in 1991, followed by the gift of their collection in 1997. The Mastersons’ prior gifts to the MFAH included extensive holdings of Worcester porcelain. Located in River Oaks on property sold to the Mastersons by Ima Hogg in 1952, Rienzi served as a hub of the city’s cultural affairs. Harris Masterson III and Carroll Sterling are pictured here at their January 1951 wedding with Carroll’s children, Bert and Isla.

MS61:01, box 24, folder 5

Today the MFAH hosts the International Center for the Arts of the Americas and twelve curatorial departments including Modern and Contemporary Decorative Arts and Design, established in 2003. In 2007, the department acquired from New York-based scholars and gallerists Garth Clark and Mark Del Vecchio more than 375 international ceramic works signifying the diversity found in this field.

Beatrice Wood (1893-1998), who was active in the studio even beyond her 104th birthday, is among those represented in the Garth Clark and Mark Del Vecchio Collection and Archive. Wood’s charm and sense of humor are illustrated in this letter written from her California home to Garth Clark and Mark Del Vecchio, January 5, 1994.

Take a brief online tour through MFAH history: from the invitation for Homer Gaudens' address in 1924 inaugurating the Houston Art League that would become the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; through the desegregation of the museum's programming and audiences by founding MFAH director James Chillman; years of civic-minded patronage by the Hogg, Straus, Beck, and Masterson families; and 70 years of distinctive building expansions by architects William Ward Watkin, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Rafael Moneo.

A House Becomes a Museum: Bayou Bend and Miss Ima Hogg

Bayou Bend, now a museum of American decorative arts associated with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, was built along Buffalo Bayou in the planned community of River Oaks newly established by the Hoggs outside the existing city limits. The house was designed by Houston's leading residential architect John F. Staub. Construction began with the laying of the cornerstone in 1927 and concluded in December 1928. Staub's plan incorporated a number of architectural styles: the symmetry of 18th century Georgian, the romance of Spanish Creole, elements of Southern plantation houses, and interiors based on Colonial homes in the North. Photo: Southern Architecture Illustrated (Atlanta, GA: Harman Publishing Co., 1931)

Bayou Bend was intended as a home for Miss Ima Hogg (pictured c. 1956) and two of her brothers, Will and Mike. But less than a year after they moved in, Mike married and moved to the house next door, and Will died unexpectedly the following year. Miss Ima and her growing collection of American furniture were left as sole occupants. She had begun collecting in 1920, always with the intention of someday giving the objects to a Texas museum. “Having made Houston my home of course I thought of our Museum here first, and some of my best pieces have already been accepted by the Museum, though there has been no way to display them there. Gradually I began to realize the restricted space at the Museum would most certainly prohibit the use of my increasingly large collection,” she wrote in 1960.

Photo: Conway Studios Corp. (NY), MS21-054

Indeed, Houston’s museum, shown here in the 1930s, was young and with limited square footage to display the furniture. It was Ray Dudley, while president of the MFAH from 1941 to 1943, who first suggested to Miss Ima that she consider donating the house as well as its furniture to the museum. The idea appealed to her despite the challenges that the donation would present. Lengthy negotiations with the museum and her River Oaks neighbors resulted in MFAH acceptance of the gift in 1957.

Her first thirty years of collecting was a solitary pursuit. It was not until the 1953 annual Antiques Forum held in Colonial Williamsburg that she met and befriended a number of others who shared her passion for American decorative arts. Among these were Henry Francis du Pont, Henry and Helen Flynt, Electra Webb, and Katharine Prentis Murphy. In this photo, Miss Ima (center) stands with Katharine Prentis Murphy and John Graham at the 1962 Williamsburg Antiques Forum. Photo: unknown photographer, MS2114-002-021B

Once the MFAH accepted the Bayou Bend gift, much work had to be done to transform the home into a museum. Miss Ima’soriginal idea of displaying her furniture in traditional museum galleries had not required all of the accessories to go along with the period furniture. So, in addition to the Colonial American paintings she had begun to collect in the 1950s, she added ceramics, glass, silver and pewter to her wish lists. Miss Ima, who had worked closely with Staub in designing the house in the 1920s, was painstaking in her efforts to redesign and rearrange the rooms in her home. In the fall of 1960, she invited a number of her collecting friends and art history experts to serve on an advisory committee to assisther with the details.

BEFORE: LIBRARY, c. 1948

The Hoggs were a well-educated family. Miss Ima studied psychology at the University of Texas; Will and Mike both earned law degrees from there as well. Though not visible in this photograph, one side of Bayou Bend’s library was lined with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, reflecting their interest in history, music, and literature. A print depicting the Battle of Buena Vista (Mexican-American War) hung above the fireplace and eighteenth century Windsor chairs surrounded a small table.

AFTER: PINE ROOM, c 1966

The Pine Room, as the library was renamed, was originally designed by Staub with woodwork based on that in the Metcalf Bowler House in Rhode Island. Eighteenth-century interiors did not have built-in bookshelves and so these were replaced with paneling. The furniture in this room was replaced with examples from New England in the William and Mary style (1690-1730), such as the Boston high chest on the left. Miss Ima selected mezzotint portraits of William and Mary to hang above the fireplace.

BEFORE: DRAWING ROOM, c. 1946

Miss Ima’s collecting interests did not lie only with American decorative arts. In her home she interspersed pueblo ceramics and modern works on paper among her antiques. Pablo Picasso’s Bottles and Grapes (1922) hung above her piano in the Drawing Room. Miss Ima gave the Picasso and more than eighty other drawings, prints, and watercolors to the MFAH in 1939. (Photo: unknown photographer, MS21-035)

AFTER: DRAWING ROOM, c. mid-1970s

The Neo-Palladian mid-eighteenth century architectural details of the Drawing Room—scrolled pediments above the doorways, based on those at Shirley Plantation in Virginia, and dentil molding—were also part of Staub’s original design. Miss Hogg replaced the chandeliers with English examples. The furniture was made in cities along the Atlantic seaboard—Boston, New York, Newport, Philadelphia, and Charleston—in the late Queen Anne and Chippendale styles (1760-1790). English Worcester porcelain, popular in America in 1760-90, sits atop a Newport tea table. (Photo: Allen Mewbourn, RG36-898:01-004)

BEFORE: BLUE ROOM , c. 1948

Staub based the paneling in the Blue Room on mid-19th century New England homes and selected the color from a fabric of the same period (seen in the curtains). The couch displayed here, an example of French Rococo revival, is attributed to the shop of John Henry Belter, active in New York in the mid-nineteenth century. Herd Boy (c. 1905), one of the collection of Frederic Remington paintings acquired by Will Hogg and gifted to the MFAH, hung in this room.

AFTER: MASSACHUSETTS ROOM, c 1975

The curtains were updated in the new Massachusetts Room. These had to be dyed three times before the right shade of blue was achieved. The Belter couch, too late to stay with eighteenth-century furniture, was removed and later placed in the Belter Parlor created by Miss Hogg in 1971. Miss Hogg moved the Chippendale double chair-back settee and its matching chairs (on the left) from the dining room where they had been used by the family for many years. The portrait above the fireplace, by an unknown artist, dates from around 1750.

Bayou Bend was officially dedicated and opened to the public on March 5, 1966. At the ceremony, Miss Ima spoke these words: “While I shall continue to love Bayou Bend and everything here, in one sense I have always considered I was holding Bayou Bend only in trust for this day. Now Bayou Bend is truly yours!” After nearly nine years of work to transform her home, she still considered it a work in progress. Until her death in 1973, she persisted in acquiring items on her wish list and sometimes even replacing pieces when a better example could be found. MFAH staff and donors continue to do the same, always with Miss Ima’s goal in mind: a place where visitors can develop an understanding of and appreciation for America’s heritage.

Walk through the history of Bayou Bend Collection and Gardens, once the family home of visionary collector, philanthropist, and Texas democrat Miss Ima Hogg and now the MFAH house museum for American decorative arts. A governor's daughter, educated in Austin, New York, Berlin, and Vienna, Miss Hogg (1882–1975) was a passionate woman and fierce competitor in the emerging field of American decorative arts.

Her legacy lives on in an unparalleled collection of American art and furnishings from the1620s to the 1870s in a John Staub-designed home set on 14 acres of meticulously crafted heirloom gardens. Further information and materials on the history of Bayou Bend are available at the MFAH Archives.

Maurice and Winifred Hirsch: World Travelers and Patrons of the Arts

Photo: MS16:06 Box 15 Folder 2

courtesy Houston Metropolitan Research Center, Houston Public Library

Maurice and Winifred Hirsch are perhaps best known in Houston for their philanthropy - giving time and money to too many organizations to name individually. However, no cause was more favored than the arts. Maurice Hirsch served as President of the Houston Symphony Society for fourteen years between 1956-1970, and as a Member of the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art and the National Council of the Metropolitan Opera Association. Winifred Hirsch, lifetime trustee, served in many roles at the MFAH including the first chair of the Art Cart program, which brought works from the Museum to recovering veterans. The General and Mrs. Hirsch are pictured here at the Houston Symphony in 1962.

Photo: Courtesy of the Houston Chronicle

Maurice Hirsch built a successful law practice in Houston - from which he never fully retired. During WWII he volunteered to renegotiate war contracts for the U.S. Army. There, he was reunited with Winifred Busby, an acquaintance from Houston. They were married in 1947 and thereafter, began a lifelong pursuit of travel and art appreciation. According to an article in the Houston Chronicle upon Winifred’s death in 1990, “The story goes – and longtime friends say it’s true – that …Gen. Maurice Hirsch presented his wife with a daily token of his devotion. Sometimes the gift was merely an amusing trinket; oftentimes it was a treasure.”

MS16:05 Box 5 Folder 11

Maurice Hirsch was a seasoned world explorer prior to his marriage to Winifred. In the fall of 1937, just as the Second Sino-Japanese War had begun in earnest, Maurice Hirsch traveled the Far East on a 96 day tour and recorded extensive notes on his impressions and experiences. In a typed manuscript titled, “Travels of Marcomaurice Hirschipolo” he describes a visit to a Buddhist temple indicating a future penchant for fine art and artifacts, “Then to the most famous of all the sights of Kamakura – the “Diabutsu” or ‘Great [Buddha]’ cast in the year 1252 of bronze with surface chisel finished, and with eyes of pure gold. The statue stands over forty-three feet in [height]. Its appeal lies not so much, however, in its size, as in the serenity of the countenance and the calmness of the posture. It is a masterful expression of, and undoubtedly to a [Buddhist], an incentive to true contemplative [Buddhism]. Above is a postcard sent during this trip to Harry Susman, a fellow partner in their law firm.

Photo: MS16:06 Box 14 Folder 39

In 1951, the Hirsches began donating and providing funds to purchase works for the MFAH, contributing an additional 103 items to the permanent collection. One of the largest of these donations was an over 80 piece collection of ancient Egyptian artifacts in 1952. The Hirsches are pictured here on a trip to Egypt earlier that year. The Hirsches were also deeply involved in the financial development of the museum. In 1981, recognizing the necessity for a superior research space available to public and staff, the Hirsches established a $500,000 endowment for what was thereafter known as the Hirsch Library.

Photo: courtesy Houston Metropolitan Research Center, Houston Public Library

The Hirsch’s extensive travels were internationally recognized as philanthropic forays to strengthen relationships between nations. In 1957 Maurice Hirsch was awarded the Italian Star of Solidarity medal for “his efforts to achieve mutual understanding through the fields of art, culture and charity.” Also pictured here is Harmon Whittington, another recipient, Dr. Alfredo Trinchieri Italian consul general of New Orleans and Mrs. Jack A. Richardson, Italian vice consul.

Workshop of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Portrait of a Gentleman, last quarter of the 17th century, marble, the MFAH, museum purchase with funds provided by General and Mrs. Maurice Hirsch.

In 1973, the Hirsches contributed funds to purchase this Italian sculpture for the MFAH. The artist credited to the work was vigorously debated at the time of attribution and continues to pose a mystery. However, museum staff—and surely the Hirsches—agreed that the masterful execution of the bust proved an essential addition to the museum's collections.

Other objects purchased for the MFAH, such as this painting, reflect the breadth of the Hirsches' travel and appreciation of the arts.

Walter Ufer’s Crossing the Rio Grande is one of six Ufer paintings given to the MFAH by General and Mrs. Hirsch. Ufer belonged to the Taos Society of Artists that operated in Taos, New Mexico from 1915-1927.

This drawing comes from a book of illustrations by Fragonard after Ariosto’s medieval romance Orlando Furioso.

The book remained intact until 1945 when the pages were separated for exhibition at the National Gallery.

Greek, attributed to the Painter of the Yale Oinochoe, Hydria (Water Jar) with Domestic Scene, c. 470–460 BC, terracotta, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by General and Mrs. Maurice Hirsch.

Photo: MS16:06 Box 15 Folder 33

Maurice Hirsch was the founding president of the Japan-America Society of Houston, a group dedicated to building a common ground between Houston, Japan and Americans with Japanese heritage. In 1981, Maurice Hirsch was awarded the Third Class Order of the Sacred Treasure for contributing to the bond between both countries. Here, on one of their many trips to Japan, Winifred and Maurice enjoy a traditional meal.

Photo: MS16:06 Box 15 Folder 42

In addition to civic service, the Hirsches also threw fabulous parties. In 1960 Winifred Hirsch was named hostess of the year. In a 1980 article in the Houston Post General Hirsch describes one of Winifred’s most amazing hostess stunts, “She invited some friends to a mountaintop picnic [in Gstaad, Switzerland] where it was just beautiful. Everyone skied except Winifred. The guests all waited and worried where the hostess was. Well, all of a sudden here she comes down in a helicopter with all the mountaintop picnic paraphernalia. She iced Champagne and caviar down in the snow and served fried chicken.” – The Houston Post May 17,1980

Photo: MS16:06 Box 13 Folder 48

After Winifred’s death in 1990 their lifetime of collected treasures were auctioned to benefit the MFAH, Houston Symphony, Houston Opera and the University of Houston School of Music. Winifred left her singular 288 item jewelry collection to the Hirsch Library as an endowment to be auctioned. She is pictured here wearing a cultured pearl diamond fringe necklace mounted in platinum which was offered at Christie’s of New York in 1991. The generous endowments of Maurice and Winifred continue to benefit the daily operation of the Hirsch Library and their numerous contributions to the permanent collection ensures an appreciation for art that long survives its donors. The Hirsch Papers are available for research at the MFAH Archives

Although the couple was deeply involved in Houston civic and social life, much of Maurice and Winifred Hirsch’s time was spent abroad. Through 36 years of marriage, they embarked on 27 world tours. Every trip provided a new opportunity to experience rare and beautiful objects. The finest artifacts often found a home in the collections of the MFAH, whether donated from the Hirsches' personal collection or purchased directly for the museum. View a selection of these gifts amid the life and travels of this prominent couple.

Houston’s Cultural Coming of Age: Festival of the Arts, October 1966

Abesti Gogora V (Song of Strength), by Eduardo Chillida, on the South Lawn. Chillida art objects © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VEGAP, Madrid. Photograph © MFAH. MFAH Archives Photography Collection.

In conjunction with the Festival, the Endowment had also commissioned a monumental sculpture by Eduardo Chillida, Abesti Gogora V, to be unveiled at artist’s retrospective exhibition opening.

Letter from Mayor’s office inviting MFAH director, James Johnson Sweeney to serve on Festival committee, 3/16/1966. RG05:01 Five Sculptures exhibition records, MFAH Archives.

Publicity for the arts festival kicked off with a press conference March 28, 1966 at the landmark Rice Hotel. In addition to MFAH director, James Johnson Sweeney, the committee consisted of Houston Symphony Orchestra conductor, Sir John Barbirolli and several cultural leaders, among them Alice Pratt Brown, Dominique de Menil, General Maurice Hirsch, Ima Hogg, and Susan McAshan.

Jesse H. Jones Hall for the Performing Arts on evening of inaugural performance by the Houston Symphony Orchestra, October 3, 1966. Photo courtesy of Houston Metropolitan Research Center, Houston Public Library, Houston, Texas. Bert Brandt Collection. MSS 0087.

Jesse H. and Mary Gibbs Jones founded the Houston Endowment in 1937. His diverse investments included sole ownership of the Houston Chronicle. Politically, he most notably served as Secretary of Commerce (1940-1945). She joined the MFAH board in 1926.

In 1962 the Endowment offered to underwrite the Jesse H. Jones Hall for the Performing Arts. It was officially presented to the City on Sunday, October 2, 1966; the gold-plated key given to the mayor actually worked.

Ima Hogg with American composer Alan Hovhaness, in Jones Hall for inaugural performance by the Houston Symphony Orchestra,October 3, 1966. MS21 Ima Hogg Papers, MFAH Archives.

Benefactress Ima Hogg, who donated her residence and American decorative arts collection, Bayou Bend Collections and Gardens, to the MFAH, was also instrumental in the founding of the Houston Symphony Orchestra. She is pictured on opening night with Alan Hovhaness, who was commissioned to compose the opening work, Ode to the Temple of Sound. Hovhaness had first received national acclaim when his Symphony No. 2, Mysterious Mountain, premiered for Leopold Stokowski’s début with the HSO in October 1955.

David Hayes sculptures displayed at Bank of he Southwest, 910 Travis. RG05:01 Five Sculptors exhibition records, MFAH Archives. Photo: Allen Mewbourn.

On the same day as the Symphony’s inaugural performance, a city-wide public art exhibition opened. Organized with the aid of the MFAH, the Houston Chamber of Commerce: Five Sculptors exhibition featured works by Alexander Calder, David Hayes, Jean Robert Ipousteguy, Marisol, and Jean Tinguely. Each was assigned a Houston bank as a venue.

Aida, inaugural performance of the Houston Grand Opera in Jones Hall, October 5, 1966. Photo courtesy of Houston Grand Opera Archives.

On Wednesday, October 5, 1966, the Houston Grand Opera held its inaugural performance, Aida, in Jones Hall. The opera featured soprano Gabriella Tucci and tenor Richard Tucker in the lead roles. HGO and the Houston Ballet would perform at Jones Hall until 1987, when the Wortham Theater Center opened in response to increased demand on the City’s cultural institutions. Jones Hall, which features a unique acoustical design comprised of 800 moveable ceiling segments, remains the active home of the Houston Symphony and the Houston Society for the Performing Arts.

The Alley Theatre under construction in 1967. Photo courtesy of the Alley Theatre.

In 1962, the Houston Endowment also provided a half-block near the Jones Hall site for the new Alley Theater. The two projects laid the cornerstone of today’s theater district, the country’s second largest.

As late as June 1965, with demolition still in progress, optimists on the building committee unrealistically hoped construction could be accelerated to meet the October deadline. Construction on an expanded site for the new theater would begin in August and conclude in 1968.

The Spring before the Festival, Eduardo Chillida, toiling in Spain, would be hard-pressed to create his monumental sculpture in time.

Telegram from Chillida to Sweeney notifying him that the Abesti Gogora V was on its way to the Spanish port of Vigo, 9/27/1966. RG05:01 Eduardo Chillida Retrospective Exhibition Records, box 36, folder 9. MFAH Archives.

Chillida’s search for the perfect stone began in mid-February. Within days he uncovered a 100 ton rose granite piece from an abandoned mine in the Spanish village of Budino. He recruited eight stone-cutters from San Sebastian, some with families in tow, to help hew the stone into the three massive pieces of his design. When at last the sculpture was finished, a fiesta was held before its transport to the port of Vigo. Each piece traveled over thirteen miles of mountain roads separately. To Sweeney’s amazement, the sculpture shipped three days ahead of schedule.

Audrey Jones Beck speaking on behalf of Houston Endowment at opening night to the Eduardo Chillida Retrospective, 10/03/1966. Photo: Budd Studios. RG05-155-336a, MFAH Archives Photography Collection.

In Houston the installation would not proceed as smoothly. Storage proved a challenge, as few warehouses could accommodate the 45-ton piece. Worse, illness prevented Chillida from traveling. Chillida’s assistant, Nicanor Carballo, and wife, Pilar, were sent in his stead.

Unveiling was scheduled on October 3, 1966, to coincide with the retrospective opening and to fall between the inaugural performances of the HSO and HGO at Jones Hall. A storm forced ceremonies inside.

Abesti Gogora V viewed through South lawn door on the day of its unveiling, 10/03/1966. Chillida art objects © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VEGAP, Madrid. Photographer © Budd Studios. RG05155-348c, MFAH Archives Photography Collection.

Requesting the Chillida commission, Sweeney wrote, “Why not a durable memorial to the Jones name through this monument which might concretely link [it] with the visual arts and the Museum, as it is already in sympathy and through earlier contributions.” Time strengthened the ties well beyond his vision, culminating in the naming of the Audrey Jones Beck building.

Abesti Gogora V has remained in place on the South lawn since its installation in 1966, a testimony not only to the Chillida’s artistic expression, but to the time when Houston realized its cultural aspirations.

As the Festival of the Arts kicked off in October 1966, Houston celebrated its cultural coming of age. The keystone of the festivities—which engaged a multitude of Houston’s art organizations, large and small—was the opening of the Jesse H. Jones Performing Arts Center, funded and presented to the city by the Houston Endowment.

The Edward J Wormley Archive: “To Hold Fast to What Is Good”

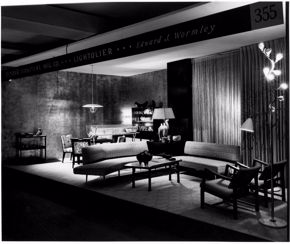

The MFAH Archives acquired the Edward J Wormley Collection, a gift of the John R. Eckel, Jr. Foundation. Although considered a Modernist, Edward J Wormley (1907–1995) created affordable, stylish furnishings for American consumers who had neither the budget nor taste for pure Modernism. The Wormley Collection comprises more than 3,000 glass and film slides as well as photographic prints and textual records including catalogues, ephemera, correspondence, and clippings. A special feature, with a slideshow of images, is available here. Researchers are invited to contact archives@mfah.org for additional information.

Treasures from Egypt’s Golden Age

King Tut ruled for only nine or ten years, until 1343 B.C when he died at age eighteen. The actual cause of his death remains unknown. The preservation of his tomb, rather than his short-lived reign, has made him legend among the pharaohs.

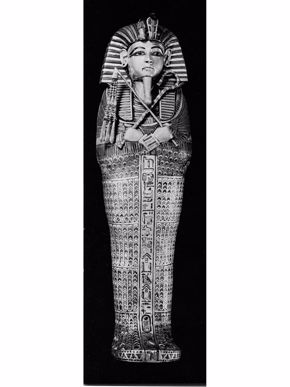

This miniature gold coffin, like the actual coffin, represents a mummified king with his arms crossed on his chest, holding the crook and flail, symbols of high office. This miniature is made of solid gold inlaid with carnelian, lapis lazuli and colored glass. (RG05:01 Tutankhamun Treasures exhibition records, MFAH Archives)

King Tut's tomb was discovered by British archaeologist Howard Carter, as part of the exploration of the Valley of Kings at Thebes in 1922. Although the outer chamber had been raided shortly after Tut’s death, debris from other tombs had covered the entrance to the inner tomb, protecting it from looters. Here, visitors examine a spouted libation vase of dark blue faience, inscribed with the royal names in white. Two smaller objects are also inscribed: the pear-shaped vase bears the throne name and the personal name of the king in turquoise, and the cup is inscribed with the personal name, Tutankhamun, in white.

The 1962 tour marked the first journey out of Egypt for the treasures from King Tut’s tomb. The Egyptian Museum allowed the objects to travel in order to draw attention to the fate of the temple of Abu Simbel. Built by Ramses II approximately 60 years after the reign of King Tut, this temple faced ruin under 200 feet of water from the construction of the Aswan High Dam. Cairo University professor Ahmed Fakhry traveled with the exhibition.

Although Texas Governor Price Daniel sent his regrets from the campaign trail, many dignitaries were in attendance for the exhibition preview, including the British Consul General, whose response letter you see here. Chair Mrs. Elva Kalb Dumas, along with Mrs. Carey Croneis, Mr. and Mrs. Harry Hassan, Mr. and Mrs. John T. Jones, and General Maurice Hirsch welcomed a crowd of trustees, press, university presidents, ambassadors, and museum members who enjoyed fruit punch and toured the exhibition prior to the opening.

The gold dagger and sheath were found in the wrappings of the mummy. The hilt is decorated with granulated gold and inlaid with colored glass and semi-precious stones, and the face bears an embossed scene of wild animals that forms a subtle interlacing pattern.

The audio-visual department of the University of Houston in conjunction with KUHT Film Productions produced a short film of the exhibition during its display at the MFAH. Ruth Pershing Uhler, MFAH curator of eduction, termed Tutankhamun, the Immortal Pharaoh “excellent” and noted that it was on view at other institutions hosting the exhibition following Houston. Pictured on the postcard advertisement for the film: this alabaster lid is from one of the compartments of the “canopic” chest, in the form of the king’s head. The headdress represented is the same as that worn by the king on the inner gold coffin.

A young visitor, exhibition catalogue in hand, examines a statuette of gilt hardwood representing the hawk-headed god Hor-khenty-khem. The face is inlaid with blue and red glass. The pedestal is of wood covered with black resinous material.

“I have seen people of all ages return several times to see the treasures.”

Tutankhamun Treasures, a 1962 loan exhibition from the Department of Antiquities of the United Arab Republic

Half a century ago, treasures from the tomb of King Tut first visited the United States in an exhibition from the Egyptian Museum, sponsored by the American Association of Museums and circulated by the Smithsonian Institution. On display from this significant period in Egyptian art: 34 precious objects and 18 photographs, which traveled to 15 U.S. museums over a two-year period. From March 16 to April 15, 1962, visitors to the MFAH South Garden Gallery had their first glimpse of a miniature gold coffin representing the mummified king; amulets and rings worn by the mummy; and a ceremonial crook, a symbol of high office.