A trove of Georgia O’Keeffe’s photographs on view for the first time in Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, exhibition this October

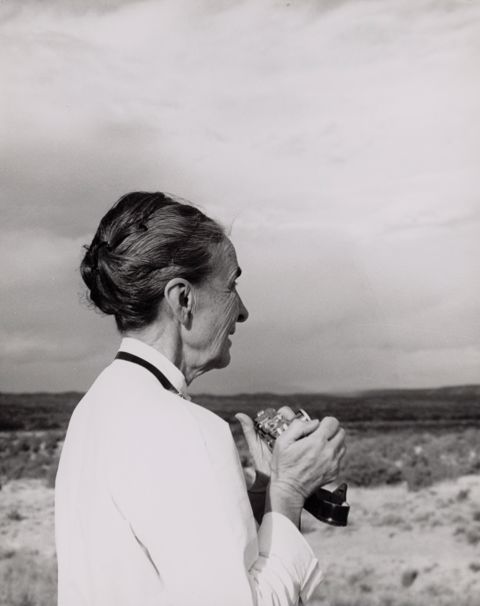

Todd Webb, Georgia O’Keeffe with Camera, 1959, printed later, inkjet print, Todd Webb Archive. © Todd Webb Archive, Portland, Maine, USA

Nearly 100 photographs from newly examined archive reveal American icon’s Modernist approach to medium in Georgia O’Keeffe, Photographer

HOUSTON—July 21, 2021—Georgia O’Keeffe is a groundbreaking figure of American Modernism, widely recognized for her paintings of New York skyscrapers, radical depictions of flowers, and stark landscapes of the American southwest. Less known is that she quietly honed a photography practice just as distinct as, yet complementary to, her paintings and drawings.

This October, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, presents the first exhibition devoted to O’Keeffe’s photographic practice with the debut of Georgia O’Keeffe, Photographer. Organized in partnership with the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, the exhibition reveals the wider scope of the artist’s career through some 90 photographs from a previously unstudied archive—a discovery led by MFAH associate curator of photography Lisa Volpe. Photographs in the exhibition will be complemented by 17 paintings and drawings of landscapes, flowers, and still lifes from public and private collections across the country.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Photographer will be on view in the Upper Brown Pavilion of the MFAH Caroline Wiess Law Building from October 17, 2021, through January 17, 2022, before travelling to the Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts; the Denver Art Museum; and the Cincinnati Art Museum.

“Georgia O’Keeffe has long been the subject of exhibitions, portraiture, and volumes of scholarship. She captivated the art world with her works on paper and canvas, yet her photography has never been studied or known despite being essential to her practice,” said Gary Tinterow, Director, the Margaret Alek Williams Chair, MFAH. “We are pleased to present this revelatory exhibition and expand appreciation of one of the most innovative and expressive artists our culture has produced.”

While Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) forged a career as one of the most significant painters of the 20th century, she also had a lifelong connection to photography. Captured on film throughout her life—in early family photos, travel snapshots, and portraits by a cavalcade of photographic artists including her husband, Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946)—O’Keeffe was no stranger to the medium. She expressed her unique perspective through all aspects of her life, and by the time she began her photographic practice in the mid-1950s, her singular identity and artistry were well developed.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Photographer is the culmination of three years of research led by Volpe, who analyzed hundreds of works in different collections and identified more than 400 photographic images by O’Keeffe. Volpe attributed, dated, and catalogued the photographs by examining small details in the images and analyzing the artist’s distinct style.

“In her 1976 book, O’Keeffe mentions her use of photography. Yet her mastery of painting stymied any research into this area for decades. It was a part of her artistic practice waiting to be examined,” Volpe said. “This exhibition reveals the ways in which she used photography as part of her unique and encompassing artistic vision. She claimed the medium for herself and her own artistic use—a radical act late in her career that begs for continued scholarship.”

The exhibition is organized around key tenets of O’Keeffe’s photographic approach: reframing, the rendering of light, and seasonal change.

Reframing views through the lens of her camera, Georgia O’Keeffe saw her environment as an array of possible shapes and forms. Moving from right to left, angling the camera from high to low, or turning it vertically and horizontally, she composed and recomposed her photographs to find harmonious compositions. Prints from O’Keeffe’s serial captures of the Natural Stone Arch near Leho’ula Beach, ’Aleamai, Hawaii are a highlight, demonstrating the artist’s intuitive search for the ideal relationship of expressive forms.

On paper, canvas, or in a photograph, dappled light and dark shadows are not merely fleeting effects for O’Keeffe. They provide weighty and essential forms. Sensitive to this formal potential, the artist often photographed the same view throughout the day to create varying compositions. A striking example is O’Keeffe’s 1964 Forbidding Canyon, a series of five Polaroids that capture changing light between two rock faces. Photographs of her beloved Chow Chows also express such possibilities, contrasting dark dog fur against the sun-washed landscape to find the tension between depth, flatness, realism, and abstraction.

O’Keeffe also explored seasonal changes by photographing her environment of evolving foliage and light year-round. Her photographs of the Chama River and a kiva ladder in her New Mexico home capture changes in vegetation, precipitation, and sunlight. Similarly, O’Keeffe regularly photographed the jimsonweed around her home, watching as the trumpet-like flowers obeyed both the cycle of the seasons and a shorter daily cycle, opening in the afternoon and closing with sunrise, from late summer until first frost. O’Keeffe’s jimsonweed prints signal the artist’s ongoing fascination with the transformations of nature.

Organization & Funding

This exhibition is organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, with the collaboration of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe.

Generous support provided by:

Rand Group

About the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Established in 1900, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, is among the 10 largest art museums in the United States, with an encyclopedic collection of nearly 70,000 works dating from antiquity to the present. The Museum’s Susan and Fayez S. Sarofim main campus comprises the Audrey Jones Beck Building, designed by Rafael Moneo and opened in 2000; the Caroline Wiess Law Building, originally designed by William Ward Watkin, with extensions by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe completed in 1958 and 1974; the Lillie and Hugh Roy Cullen Sculpture Garden, designed by Isamu Noguchi and opened in 1986; the Glassell School of Art, designed by Steven Holl Architects and opened in 2018; The Brown Foundation, Inc. Plaza, designed by Deborah Nevins & Associates and opened in 2018; and the Nancy and Rich Kinder Building, also by Steven Holl Architects, opened in 2020. Additional spaces include a repertory cinema, two libraries, public archives, and facilities for conservation and storage. Nearby, two house museums—Bayou Bend Collection and Gardens, and Rienzi—present American and European decorative arts. The MFAH is also home to the International Center for the Arts of the Americas (ICAA), a leading research institute for 20th-century Latin American and Latino art. mfah.org

Media Contact

Melanie Fahey, publicist

mfahey@mfah.org | 713.800.5345