The Dragon in Islamic Art

By Anushka Hosain

Curatorial Assistant, Art of the Islamic Worlds

A pair of rampant cream-colored dragons claw their way up the spectacular 21st-century Dragons of Karabakh carpet by Azerbaijani artist Faig Ahmed, installed in the center of the Art of the Islamic Worlds galleries. Its historical inspiration, a 17th-century Caucasian “dragon” carpet, with three pairs of dragons, is installed nearby. In the Blue-and-White Ceramics Gallery, a speckled dragon wraps around a 17th-century Safavid Iranian ceramic huqqa base. In the Calligrapher’s Tools case, a gleaming serpentine dragon coils through floral vines on a mother-of-pearl Ottoman makta, or pen rest. In 2024, the Year of the Dragon in the Chinese zodiac, the MFAH invites you to view the many ferocious, protective, and peaceful dragons in Islamic art. Though the Chinese dragon may be more familiar to viewers, dragons are also featured prominently in Islamic art. At times similar in looks and behavior to their Chinese cousin, in other instances a direct descendant of ancient West Asian progenitors, the dragons on view in the Hossein Afshar Galleries for Art of the Islamic Worlds are exemplary cross-cultural creatures.

Is the dragon in Islamic art a force of good or evil? A source of terror or a fount of protection? It is precisely this ambiguity and dualistic nature that gives the dragon such power. In West, Central, and East Asia, the dragon is strongly associated with the elements, especially water and fire. Its liminal nature positions it as an ideal beast to stalk borderlands and contested regions, and as a potent talismanic force to guard gates and doorways. In some cultures, the dragon has been appropriated as the symbol of power par excellence, as with the Chinese dragon, which is associated with the Chinese Emperor. In Islamic art too, the dragon often appears in princely and heroic settings.

Beastly Origins

The origins of the dragon are shrouded in ancient darkness. Serpent and snake, winged and scaled, fork-tongued, fire-breathing, coiling, and writhing, protector or wreaker of havoc: the dragon has taken many forms as it has moved through time and across space. In stories told over the course of human history, the dragon has been mythological, astrological, talismanic, heraldic, and metaphorical.

According to an ancient Mesopotamian myth, in the beginning there was watery, primeval chaos, which took the form of a sea-dragon goddess named Tiamat. She was slain in fierce battle by the god Marduk, who used her body to form the heavens and the earth. In an ancient Indo-Aryan myth, a ferocious dragon who threatened to withhold rain was killed by a god named Vrta-han, ‘slayer of obstacles.’ Vrta-han became Wahrām, an Iranian god, and then Bahram, a Sasanian king and hero of the Shahnama, or Book of Kings, an epic 10th-century Persian tale.

From these ancient monsters, how do we arrive at the contemporary Dragons of Karabakh? The dragon in Islamic art can be roughly classified in two types: the first, a direct descendant of the fearsome West Asian dragon; the second, a protective or apotropaic dragon (the third, the astrological dragon which takes on features of both previous types, cannot be discussed here for considerations of space). All of these dragons could exist simultaneously, though their popularity rose or fell as artistic models and forms changed over time.

The Hero and the Dragon

“… How you have no fear, and face alone

Dragons and demons and the dark unknown”

—The Tale of Sohrab, from the Shahnama

Deriving from the ancient Semitic and Indo-Aryan models, this Iranian dragon is a malevolent force. The dragon represents chaos threatening humankind and the balance of existence, an evil force that must be vanquished by a god or a hero. This is the type of dragon seen in the Shahnama, being slain by the heroes Bahram, Rustam, or Gushtap.[i] The imagery of the dragon in the Shahnama illustrations is particularly interesting. With their rapid conquests of East, Central, and West Asia in the 13th century, the Mongols linked far-flung regions and facilitated transfers and exchanges of peoples, ideas, technologies, and artistic forms on a continental scale. The earliest illustrated Shahnama manuscripts, produced under the Ilkhanid Mongol rulers of Iran in the early 1300s, show the hero battling a creature in the form of the Chinese dragon, but without any auspicious Chinese connotations. Reflecting the adaptation of Chinese artistic forms into Iranian culture,[ii] the dragon has gained a Chinese appearance but underneath is still the malevolent beast of myth that must be vanquished by Bahram, smiter of obstacles, in a replay of the ancient battle between god and monster.

This dragon could, however, coexist with the Chinese dragon, which was occasionally imported with its original meanings intact. The dragon and dragon-slayer pair is akin to another famous combatant and partner of the dragon: the phoenix. The phoenix and dragon pair is a classic Chinese emblem symbolizing the yin and the yang, or the balance of powers in the universe. The pair are illustrated in a folio of our Falnama, or Book of Omens, a manuscript used for divination. The Prophet Suleiman, the Biblical Solomon, who in Islam is considered a universal sovereign and blessed with power over natural and supernatural creatures, is enthroned with Bilqis, Queen of Sheba, as an assortment of creatures including the dragon, the phoenix and divs, or demons, pay obeisance. On the other Falnama folio, a dragon adds fire to the torment of sinners in hell.

Solomon and Bilqis Enthroned, from a Falnama, Safavid Iran, mid-1550s-early 1560s, ink, opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper, The Hossein Afshar Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

The Flames of Hell, folio from a Falnama, Safavid Iran, mid-1550s-early 1560s, ink, opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper, The Hossein Afshar Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

The dragon is sometimes paired with other combatants such as the demon in the painting below, and with its Chinese partner, the phoenix, as seen soaring in the border.

Attributed to Mu'in Musavvir, Demon and Dragon in Combat, Safavid Iran, mid-17th century, ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, The Hossein Afshar Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

The Apotropaic Dragon

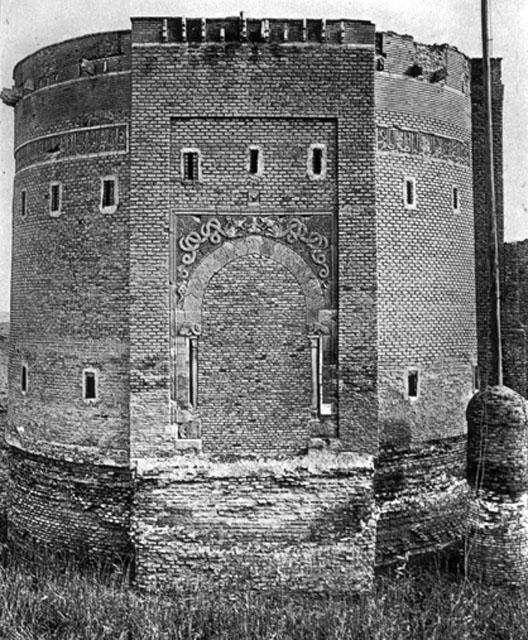

Dragons have long served protective functions over entryways and thresholds. The dual nature of the dragon makes it an especially potent device for guarding gates, walls, and doorways. One of the most outstanding examples is the famous Talisman Gate of Baghdad, built during the Abbasid period in 1220 and destroyed in 1917.

Talisman Gate, Baghdad, 1222, exterior view with bricked-up entrance. Photos from Archnet

Detail, with winged dragons and a human figure grasping their tongues, likely representing a glorious conqueror.

The dragon’s power functions through the notion of symmetry, or like-counters-like, i.e., the dragon’s ferocity keeps out evil.[iii] This dragon typically has a knotted body, the knot being an ancient apotropaic form, and is frequently paired.

“Rustam’s banner, with its dragon device, seemed to eclipse the sun; wherever he rode, severed heads fell to the ground” (from Firdawsi’s Shahnama).

The talismanic element of the dragon can be seen on the Ottoman military banner in our collection. Here, the quillon of the bifurcated sword of ‘Ali (559-661), cousin of the Prophet Muhammad and the second most important Muslim figure, takes the form of paired, knotted dragons, which enhance the already powerful talisman of the sword.

“Rustam’s banner, with its dragon device, seemed to eclipse the sun;

wherever he rode, severed heads fell to the ground”

—Firdawsi’s Shahnama

Banner, Ottoman Türkiye, late 17th century or later, silk with metal thread, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by Rania and Jamal H. Daniel; Lily and Hamid Kooros; Dr. Aziz Shaibani; and the Director's Accessions Endowment.

Banner (detail), Ottoman Türkiye, late 17th century or later, silk with metal thread, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by Rania and Jamal H. Daniel; Lily and Hamid Kooros; Dr. Aziz Shaibani; and the Director's Accessions Endowment.

The paired dragons on these ‘alams, or standards, which were paraded in religious ceremonies as emblems of power, served a similar function. Both objects are on view in the Hossein Afshar Galleries and The Al-Sabah Galleries, respectively.

Standard (‘Alam) (detail), Iran, Safavid, 17th century, steel, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Vahid and Cathy Kooros.

Standard, Iran, 1712–13, steel, bronze and brass, The al-Sabah Collection, Dar al-Athar al Islamiyyah, Kuwait.

The protective dragon reigns in Central Asia, where its beneficent aspect is often associated with rain and fertility. This connection is seen on the handle of a delicately engraved and inlaid Timurid jug, on view in the Hossein Afshar Galleries for Art of the Islamic Worlds.

Jug, Iran, Timurid, 1495–96, brass; cast, engraved, and inlaid with gold, silver, and black compound, The Hossein Afshar Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

The Dragon Carpets

The two ‘dragon’ carpets currently on view in the galleries are from the Caucasus. Like Central Asian and Turkic carpets, with whom they share many features, Caucasian carpets tend to be of striking, vibrant colors, with sharp, angular designs, and often feature highly stylized and abstracted vegetal and zoomorphic designs. The historical carpet was produced in the 17th-century, when the Caucasian region was under Safavid control. The Safavids established numerous carpet-making factories in the region; these carpets were widely traded across the globe. Today, about 150 dragon carpets are known, mostly in museums.

Here, the dragon is presented in its totemic, benevolent form, alongside highly geometricized lotus blossoms and on a bold red color field, all auspicious elements transmitted along the Silk Roads that would have further bolstered the carpet’s symbolic value.

Carpet, Caucasian, 17th–18th century; wool and cotton; The Hossein Afshar Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Returning the viewer to the present is Faig Ahmed’s remarkable Dragons of Karabakh, an artwork fascinating in concept, execution, and form. Dragons and other motifs from the historical carpet are presented in complex layers of significance. Faig Ahmed’s works have political overtures, drawing on his experience of growing up under Soviet rule, when local customs were highly discouraged. In making this carpet, the artist returned to historical techniques and traditions. Though it was designed on a computer, the artist requested and received the approval of the local Azeri women weavers, who wove it by hand using traditional vegetable dyes.

Faig Ahmed, Azerbaijani, Dragons of Karabakh, 2021, cotton warp and weft, wool pile; symmetrical knot, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment.

As the carpet melts and pools on the floor, it is suggestive of that watery, primeval chaos of the most ancient dragons mentioned at the beginning of this essay. In this highly contemporary work, it seems we have come full circle, witness to the occurrence and recurrence of artistic ideas and motifs over time.

[i] The Shahnama, or Book of Kings, is a monumental Persian epic poem narrating the history of Iranian kings from mythological beginnings to the Arab conquest of 651. Written by the poet Firdawsi (935–1020) in 50,000 rhyming couplets, the epic offers models of exemplary conduct and just rulership that subsequent rulers sought to emulate. Lavish copies were commissioned by Persianate kings from the medieval to the early modern periods. The MFAH holds two folios from the magnificent illustrated Shahnama of the Safavid emperor Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524-76), along with folios from other Safavid, Mongol, Injuid, and Turkmen manuscripts.

[ii] The Arts of the Islamic Worlds galleries show Abbasid (750-1250) ceramic works influenced by Tang (618-907) objects alongside numerous Safavid works such as the huqqa base mentioned earlier. For more information on the vibrant cross-cultural exchanges that led to the development of blue-and-white ceramics, visit our exhibition page for Between Sea and Sky: Blue and White Ceramics from Persia and Beyond (November 21, 2000-May 31, 2021).

[iii] For more on this concept: Persis Berlekamp, “Symmetry, Sympathy, and Sensation: Talismanic Efficacy and Slippery Iconographies in Early Thirteenth-Century Iraq, Syria, and Anatolia.”