Shine On! Art Inspired by the Sun September 5, 2018

Hans Hofmann, Fiat Lux, 1963, oil on canvas, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by Mrs. William Stamps Farish, Sr., by exchange. © Renate, Hans and Maria Hofmann Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Akan, Ghana, Soulwasher’s Badge, early 20th century, gold, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by Alfred C. Glassell, Jr.

Ancestral Pueblo (Anasazi), Jeddito Black-on-Yellow Bowl with Sun Burst Design, 1250–1350, earthenware with slip, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Meredith J. Long.

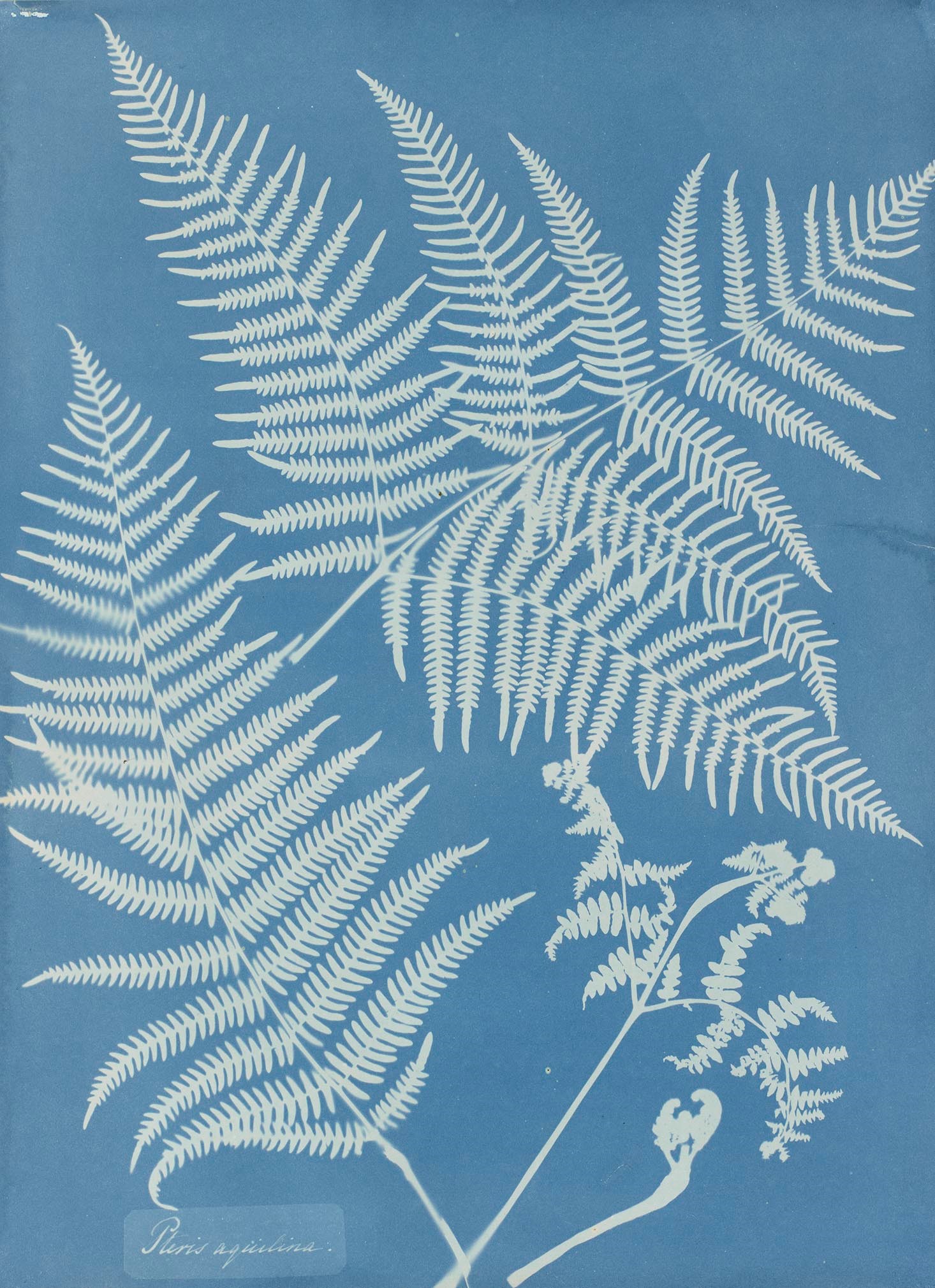

Anna Atkins, Pteris aquiline, 1851, cyanotype, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by The Brown Foundation, Inc., The Manfred Heiting Collection

Iran, Astrolabe, late 17th−18th century, engraved brass, The al-Sabah Collection, Kuwait.

Joan Mitchell, Tournesols (Sunflowers), 1976, oil on canvas, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, bequest of Caroline Wiess Law.© Estate of Joan Mitchell

“My aim in painting is to create pulsating, luminous, and open surfaces that emanate a mystic light.” —Hans Hofmann

Summer may be winding down, but Houstonians know all about the endurance of the Texas sun. Of course, we aren’t the only ones who bask in the warm glow almost all year round: Artists use their imaginations to orbit the sun as inspiration.

Here are a few works from the MFAH collections and The al-Sabah Collection that shine brightly!

Akan, Soulwasher’s Badge, 1900–1930

The Akan peoples of West Africa considered gold to be an earthly counterpart to the sun, as well as the manifestation of kra, or the vital force of life. Worn by akrafo (soul washers)—beautiful young men and women who were selected to serve as royal attendants—soulwashers’ discs or badges were protective emblems.

Ancestral Pueblo (Anasazi), Jeddito Black-on-Yellow Bowl with Sun Burst Design, 1250–1350

The Ancestral Puebloan peoples of the American Southwest were keen observers of astronomy, and archaeological remains suggest they carefully tracked seasonal cycles. The sun was vitally important to their calendar, which told them when to plant and harvest crops. Vessels embellished with important symbols—such as the boldly painted sun bursting from the center of this bowl—transcended practical purposes through often-elaborate designs.

Anna Atkins, Pteris aquilina, 1851

Using the cyanotype process—a cameraless method of photography invented in 1842 and later used for architects’ blueprints—English botanist Anna Atkins placed each specimen on a sheet of sensitized paper, sandwiched the paper behind glass, set it in the sun, and developed the resulting image in water. Atkins made thousands of cyanotypes and bound them in volumes that were the world’s first photographically illustrated books.

Hans Hofmann, Fiat Lux, 1963

Fiat Lux, which can be translated from Latin as “Let there be light,” demonstrates the radiance that Hans Hofmann brought to his later-career paintings. The center of this composition explodes with a generative burst of vibrant yellow, and the entire surface is energized by the artist’s expressive brushwork.

Iran, Astrolabe, late 17th−18th century

The word for this navigation tool, “astrolabe,” comes from the Greek words for “star” and “taker.” For centuries, Muslims used astrolabes—including this example, on view in Arts of Islamic Lands: Selections from The al-Sabah Collection, Kuwait—not only to designate the direction of Mecca and prayer times, but also to determine the altitude of stars, the sun, the moon, and the other planets.

Joan Mitchell, Tournesols (Sunflowers), 1976

Among the second wave of Abstract Expressionist painters, Joan Mitchell left New York for France in 1959. Eventually, she settled in Vetheuil, near Claude Monet’s Giverny studio, where she launched into her Tournesols (Sunflowers) series of paintings. She said she wanted her paintings “to convey the feeling of the dying sunflower,” rich with color and a sense of the passage of time.