The Kodak Snapshot: A Conversation with MFAH Curator Anne Tucker (part 2 of 3) April 3, 2012

In the wake of the Eastman Kodak Co. filing for bankruptcy, I sat down for a chat with Anne Wilkes Tucker, the Gus and Lyndall Wortham Curator of Photography at the MFAH. She discussed the history of Kodak and the monumental news that “something that huge is gone.” In part two of our conversation, Tucker explains how the Kodak snapshot changed the way artists and historians viewed the world around them:

"Aesthetically, artists and photographers very quickly found a charm in the fact that most of the people who were using the Kodak [camera] were not sophisticated picture makers, so there were these wonderful mistakes—people’s heads being cut off, bodies being cropped in half, somebody walking in front of the lens—that artists began to use. Starting with the Impressionists, they began to see this as a different picture aesthetic. Photographers and painters responded. It was charming, it was fun. For the art world, snapshots were a wonderful infusion of a new way of seeing. Not all of it intentional, but recognized by artists as valuable.

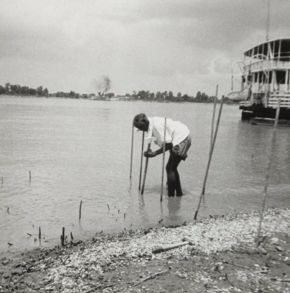

"When I first came into photography, the first time I saw work by Robert Frank, who is a major artist in our collection, I was stunned to see he had photographed a man I knew in my childhood: an elderly black man positioned by the edge of the Mississippi River in my town, beckoning people to come and be baptized. I knew the old man, I had talked to him, I was quite fascinated by him. And I had photographed him myself. My photograph is not Robert Frank’s photograph. It was an immediate lesson in what a great artist can do with the same subject that an amateur does.

"The other thing about snapshots is that for any historian—cultural historian, historian of a locality, historian of clothing, historian of how a landscape has changed—snapshots are this incredible wealth of information. In World War II, the British government asked people who had vacationed in Normandy to send in their photographs of the Normandy beaches and of any buildings that could be used as landmarks by the landing forces, which were used to help plan the D-Day landing.

"When I was in graduate school in the 1960s, there was a man that worked at Kodak [whose job it] was to feed the film into the machine that processed it and made the prints. Then he would take the film out and put the photographs in a package. He told me he noticed that when people came back from a trip and had two pictures left they wouldn’t waste those two pictures. And he noticed a shift from people taking those two pictures of somebody standing by their car to people standing by their new television, because televisions were new in the home then. So there was a cultural perception that historians have used.

"What worries me as a cultural historian is that when people get new computers, they don’t download those images. Scrapbooks are being made in the Cloud or on the web. But they’re not physical objects. There’s not going to be that experience and pleasure of finding a lot of snapshots in antiques stores, or garbage cans, or on eBay. You have blogs—some of them will be saved and some of them won’t. Some are not available to the general public, they’re just available to your friends. It’s a new system. But this unique period—when these charming, small objects filtered out into the public—was rich."

Stay tuned for part three of our conversation with Anne Tucker as she gives us a behind-the-scenes look at the exhibition Snail Mail, on view through May 20.