Endangered Animal? Assessing the Light Sensitivity of Walton Ford’s “Oso Dorado” July 2, 2014

Walton Ford, Oso Dorado, 2013, watercolor, gouache, ink, and graphite on paper, Museum purchase funded by “One Great Night in November, 2013.” © 2013 Walton Ford. Courtesy the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery.

Each year the Museum adds masterpieces to the collection through “One Great Night in November,” one of this institution’s largest fundraisers in support of art acquisitions. In 2013, the event acquired Oso Dorado, a monumental watercolor by American artist Walton Ford. Painted only a few months before “One Great Night in November,” the five-foot-wide work of art was in pristine condition, with all its immediacy and freshness intact.

It’s our first priority to ensure Oso Dorado retains this freshness for generations to come. Works of art on paper can be subject to irreversible light-induced damage, a dilemma for institutions whose essential mission is to share art with the public. So the first task the conservation team faces in such instances is to evaluate the artwork as specifically as possible to determine how we can best preserve it. Only by carefully studying the work can we know how often it could be exhibited, and under what conditions.

Left to right: Advanced conservation intern Heather Brown, works on paper conservator Tina Tan, and research scientist Cory Rogge discuss the artist’s palette.

Calibrating the state of works on paper has been aided in recent years by new technologies. In the 1990s, a scientist at Carnegie Mellon University created an instrument known as a microfade tester that uses a very small, intense beam of light to slightly fade an area of color in a work of art. The color’s fading rate is compared to that of three different swatches of blue-dyed wool whose light sensitivity is known. This comparison allows scientists to predict how much light work can be exposed to before the art begins to fade.

Left to right: Menil Collection staff members Tom Walsh, Adam Baker, and Tobin Becker move the unframed “Oso Dorado” to a workbench.

Although the MFAH does not own a microfade tester, our neighbors at the Menil Collection do, and they welcomed our proposal to collaborate. Oso Dorado was transported to the Menil, where Cory Rogge, Andrew W. Mellon Research Scientist at the MFAH and the Menil, and I worked to test the lightfastness of 12 different areas of the work. All the colors we tested showed a relatively gradual rate of fading, indicating that the artwork is stable.

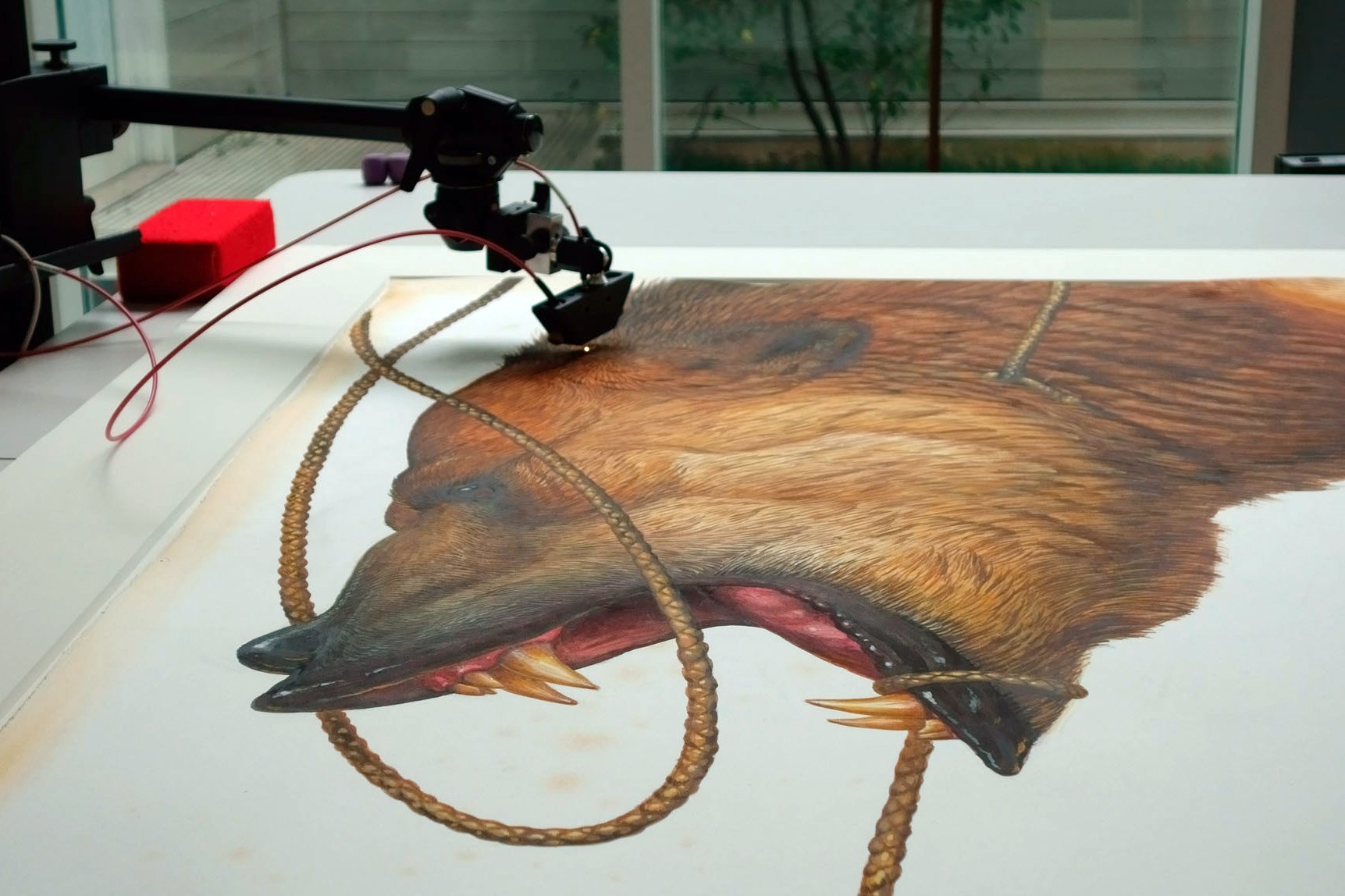

The microfade tester collects data.

Cory further analyzed pigments in Oso Dorado with X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy and verfied that the artist used watercolor containing inorganic pigments. These records not only confirm the materials of the artwork, but also establish a baseline for future studies.

Cory Rogge calibrates the microfade tester.

Oso Dorado portrays the California grizzly bear, a magnificent beast hunted into extinction in the 20th century. Ford deliberately stained the margins to give his watercolor the appearance of age, as if it were an artifact from a century past. However, with careful foresight, Oso Dorado will not become a similarly “endangered animal,” and with the knowledge gained through our studies we can plan strategically for future exhibitions of this wonderfully dramatic work of art.

Want to see more up-close looks at conservation projects? Check out Selected Case Studies for highlights.