4 Questions about “Sontag” for Author Benjamin Moser September 17, 2019

Benjamin Moser

Photo: Beowulf Sheehan

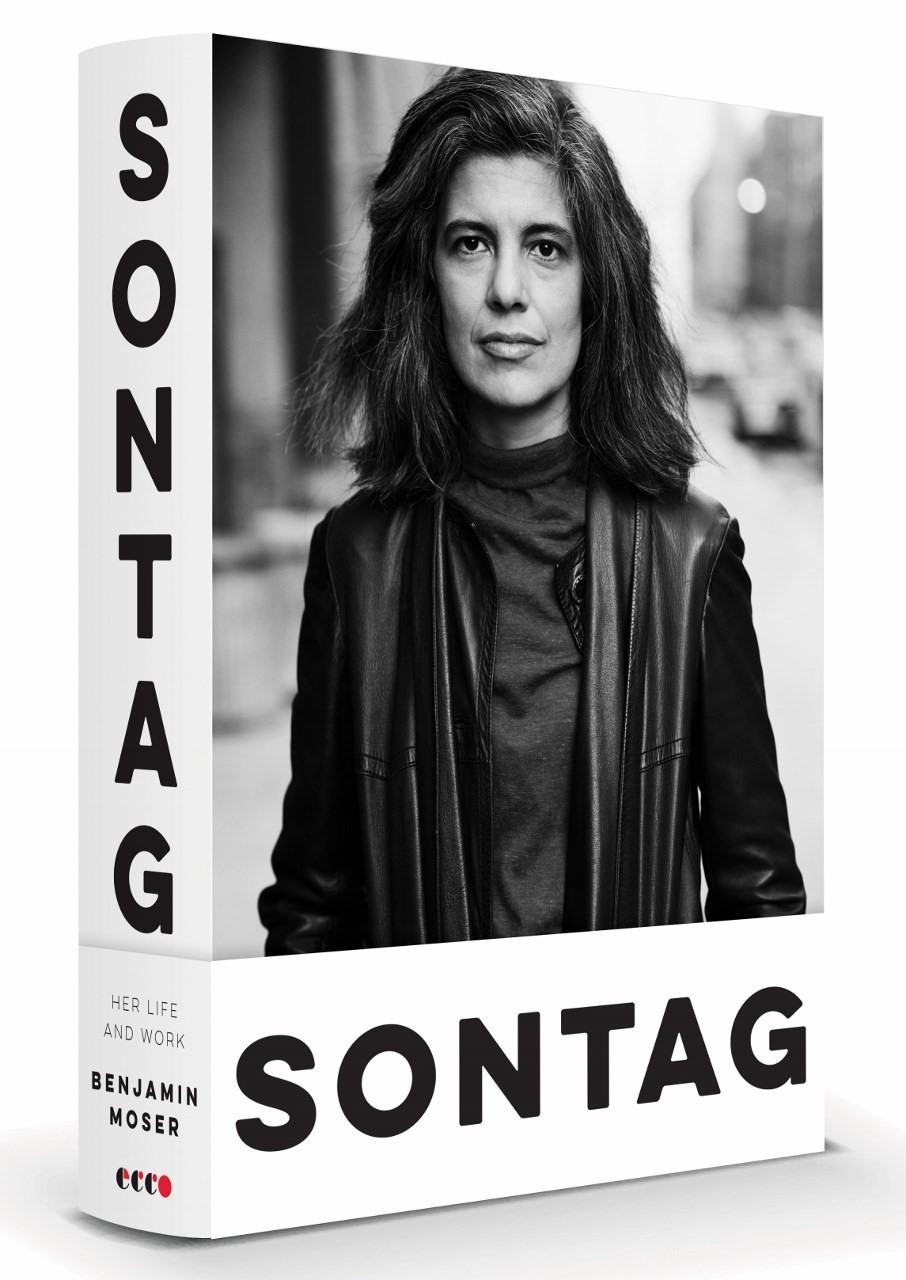

Sontag: Her Life and Work by Benjamin Moser

On Monday evening, October 7, Benjamin Moser visits the MFAH to present highlights from Sontag: Her Life and Work, his new biography of writer Susan Sontag (1933–2004). A book signing and reception follow.

Moser, who was born in Houston, previews his talk by answering a few questions about his subject’s uniquely famous life.

Why do you think Susan Sontag is still popular today?

Susan Sontag was America’s last great literary star, a flashback to a time when writers could be, more than simply respected or well-known, famous. She was an essayist, a filmmaker, a playwright, a novelist, a political activist, and that rare thing in America: a public intellectual, and a model for generations who came after her. But she once joked that she was best known for the white streak in her black hair. She was well aware that her image had become better known than her writing, and that was why she could become so many things for so many different people.

Some people saw her as the unbowed thinker, the engaged citizen, the powerful woman. Other people saw her as a sexual deviant, a sign of intellectual collapse, a traitor to America. Even now, 15 years after her death, a lot of people still love her, and a lot of people still hate her. I hope a more balanced picture can emerge—and what I’d like most of all would be for both fans and haters to read her, and to engage with her life and work.

What makes you say that Sontag was famous in a way no subsequent writer has been?

It was hard for me to understand, at first, how Susan became as famous as she did. She seemed to come out of nowhere, and by the time she was in her early thirties, she was already spotted at dinner in a posh New York restaurant with Jackie Kennedy and Leonard Bernstein. How had she gotten there? Many of her early essays are extremely difficult, partly because they assume a knowledge of an intellectual and literary world that is quite foreign to readers today—one that requires the kind of contextualizing I try to provide.

Still, even then, essays about Georg Lukács and Nathalie Sarraute and Isaac Bashevis Singer didn’t seem to be a path to worldwide fame. Yet she somehow managed to stand at the junction of art, culture, politics, and sexuality at a time that all of those things were undergoing radical changes. She became someone that a whole generation looked to in order to make sense of that changing world, and she managed to stay in the position she earned as a very young person until the end of her life, nearly half a century later.

You were the first person to speak to Annie Leibovitz about her relationship with Sontag—a relationship Sontag never publicly acknowledged, and whose difficulties you reveal. Why do you think Sontag seemed troubled by any acknowledgment of her sexuality?

Before I started working on this book, I assumed that Susan was gay in the same way I assumed she was Jewish. It never crossed my mind that she wasn’t, or that everyone didn’t know. I couldn’t imagine that anyone she knew, or any of her readers or admirers, would care either way.

But as I began looking into her life and her relationships, I learned that she had never acknowledged her sexuality publicly, and indeed she lied about it constantly. It seemed so bizarre for a woman of her worldliness and sophistication that I struggled to understand it. But she grew up in a world with extremely anti-gay attitudes. To be gay could cost you your family, your home, even your life. A book like Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt, which came out when Susan was 19, was considered to be a positive portrayal of lesbians because the women weren’t killed at the end: one just lost her child. Like many gay people, Susan never managed to shed these homophobic attitudes entirely. Because it’s one thing to know something intellectually and something else to accept it emotionally.

Why should young people read Sontag today?

The reason her work has stood the test of time is that she, more than any other American writer of her generation, gives you a key to culture. She tells you about Freud and Sartre and photography and dance and politics and war, yes. But more to the point: She helps you understand how the great modern thinkers have thought about our world, and how to live in it. She gives you their ideas, she gives you her ideas about their ideas—and then she spurs you to formulate your own.

► Hear Benjamin Moser speak on Monday, October 7, at 6:30 p.m. Pick up a copy of “Sontag: Her Life and Work” at the MFA Shop, or order by phone at 713.639.7360. LEARN MORE